Last Tuesday, Atlanta fired manager Fredi Gonzalez. It wasn’t a particularly shocking move. The Braves, stewards of the worst record in baseball, have an unhappy fanbase hungry for change. Change is what they got. Yes, it’s change for the sake of change, and it will have little effect on the 2016 Braves’ fortunes (or 2017, most likely). If the team improves, it’s because the team was bound to improve anyway. This is not a move intended to help win more games. It’s a move intended to make restless fans think the team wants to win more games. Re-shuffling of Titanic deck chairs? Certainly, but if it calms down some passengers a bit and helps them focus on survival, maybe there’s no harm to it. The Braves are unlikely to be any worse, and if fans can point their own eyes toward the franchise’s survival – specifically, the bevy of young talent still being acquired and on its way – perhaps they’ll settle down a bit as well. The timing is somewhat irrelevant. So is the interim, Brian Snitker. He gets some time to sit on a bench and manage a clubhouse. Good for him. He’s had a long career in the organization, and this is an excellent way of thanking him for it. If he’s the team’s manager of the future, we don’t know that at this point. I don’t think he is – not many great managers begin their managing careers at age 60, but at this point it’s hard to know. Furthermore, perhaps the timing even helps Fredi Gonzalez. He was dealt an unwinnable hand, and he wasn’t even allowed to really play it. He presided over some winning ballclubs, and this preserves his win-loss record a bit. He gets a paid summer off to recharge the batteries and line up another job down the road. Why would a manager with multiple trips to the postseason want or be expected to sit through a full rebuild? So really, this article isn’t so much an explanation of why Fredi was fired. We know why Fredi was fired. Managers don’t survive rebuilds, regardless of whether or not they should. This is going to be more of a look at what Frediball really was.

The Three Big Things

There are many facets of a manager’s job, but I’ve always been of the opinion there are 3 big jobs for a manager:

- Manage the clubhouse and keep the players functional, as well-rested as possible, and happy

- Put the correct players into the starting lineup

- Responsibly manage the pitching rotation and bullpen in a way that keeps pitchers useful and healthy

As for #1, it’s hard for anyone outside the organization to know how well he did. By most accounts, Fredi was well-liked in the clubhouse. Of course, the Braves are notoriously un-gossipy as an organization, so if Fredi was terrible at clubhouse management, I’d imagine we probably wouldn’t hear much about it. If he lost control of the team, I doubt we’ll know, at least until Nick Markakis‘ tell-all memoir hits shelves. So, while it’s a big requirement for the job, I don’t think it’s under the purview of outsider analysis.

#2: Put the correct players into the starting lineup. Bobby Cox always did this so well, it’s easy for Braves fans to forget just how often managers around the league can and do get this wrong. Good players too often ride benches or are stuck in platoons for this reason or that. While Gonzalez didn’t have a perfect record in this regard, and recently had his most glaring mistake in this area – giving A.J. Pierzynski the lion’s share of starts over Tyler Flowers, he generally did well. Aside from a few obsessions with the Jose Constanzas of the world, Fredi generally put the right names into the lineup each day. And remember, that’s the biggest thing. Sure, ordering them correctly would help a bit, but the names are much more important than the order they’re aligned. Fans love to harp about who should hit 4th and who should bat leadoff, and while yes, you can make mistakes with those decisions, those mistakes don’t make drastic differences in the season.

#3: Responsibly manage the pitching rotation and bullpen in a way that keeps pitchers useful and healthy. I think most Braves fans would earmark this as an area of failure for Fredi, although that’s not entirely true. Gonzalez’s rotations were typically healthy and useful. Twice in his tenure Atlanta placed in the top 5 in quality starts, once even leading the majors. His bullpen usage was a bit heavy at times, but it kept his better, less replaceable pitchers healthy. If you’re going to overwork one or the other, overwork the bullpen. As for keeping pitchers useful, Gonzalez generally adapted well to figuring out which relievers belonged in low leverage situations and which belonged in more important innings. He wasn’t perfect – his mistrust of Luis Avilan in 2014 was short-sighted and seemed wholly based on ERA, an ERA offset by a few singular meltdown innings. And then, of course, there’s THE moment. But we’ll get to that. For the most part, he did ok in this regard.

If this sounds overly glowing, I don’t mean it to be. Gonzalez was given some pretty good teams and he managed to not mess them up. In his first 4 years on the job, the Braves finished 2nd, 1st, 2nd, and 2nd (although the latter was a 79-83 “triumph” over three of the worst teams in baseball). His average place of finish for his Braves career was 2.3. Bobby Cox’s was 2.2. While strategically frustrating (we’ll get to that shortly), he still managed to limit the damage in the W-L column. The Braves still won games when they tried, more or less.

Now, let’s look deeper at his strategies.

Offensive Strategy

Stealing Bases

I don’t like looking at baserunner aggressiveness as a sign of managerial tactics, because it isn’t fair to the managers. If I had Billy Hamilton on 1st base, I’d be more aggressive than a manager with David Ortiz standing on the bag. Instead, I look at how successful runners were when they ran. With Fredi Gonzalez, there wasn’t a lot of consistency:

2011: .636 (27th in MLB) (77/121)

2012: .759 (11th) (101/133)

2013: .674 (22nd) (64/95)

2014: .742 (10th) (95/128)

2015: .676 (20th) (69/102)

2016: .615 (22nd) (16/26)

In 2012, Atlanta was outstanding at stealing bases, which was entirely thanks to Michael Bourn (42/55) and Martin Prado (17/21). In 2014, they were good again from more of a teamwide perspective, with efficient basestealers like Jason Heyward (20/24), B.J. Upton (20/27), Emilio Bonifacio (12/14), Jordan Schafer (15/17), and even Chris Johnson (6/6).

But for the most part, Gonzalez’s runners just weren’t all that efficient. It didn’t seem to matter too much. 2013’s basestealing was sub-mediocre, and it was the highest scoring offense of Gonzalez’ tenure. Base stealing is not a necessary component of offense. If you have them, use them. The Braves didn’t have them, and the Braves were never particularly steal-happy with players who needed to avoid it.

Sacrifice Bunts

First off, the sacrifice bunt, while much-maligned, isn’t all bad. It’s a perfectly acceptable strategy for pitchers at the plate with someone on base. For everyone else, it’s almost always a mistake. Let’s delve into the numbers real quick to explain why. Here are the run expectancies for each situation (specifically, it’s how many runs over the rest of the inning a team is expected to score when starting with each situation):

| 0 Outs | 1 Out | 2 Outs | |

| Bases Empty | .48 | .26 | .10 |

| 1st | .84 | .50 | .22 |

| 2nd | 1.08 | .65 | .32 |

| 3rd | 1.30 | .89 | .36 |

| 1st & 2nd | 1.44 | .89 | .44 |

| 1st & 3rd | 1.67 | 1.13 | .48 |

| 2nd & 3rd | 1.90 | 1.28 | .58 |

| Bases Loaded | 2.27 | 1.53 | .70 |

These aren’t theoretical numbers. They’re from what actually happened in the 2015 season across MLB. With a runner on 3rd and 1 out, teams scored an average of .89 runs from that point on in the inning. Now let’s talk about sac-bunts.

With a runner on 1st and nobody out, the normal run output is .84 runs. If you give up an out to move that runner to second, it lowers your output to .65 runs. That runner on 2nd is indeed more likely to score than before, but the total goes down because you’re throwing away a big chunk of your opportunity for more runs after he scores. If you’re a home team in a tie game in the 9th, bunt away because extra runs do you no good. The rest of the time, preserving the out is much more valuable than the base. As you look at the table, you see there’s no instance where a base is more valuable than the out. Outs are the clock in baseball. You’ve got 27, and you get to make them last as long as you’re able to. Giving them away is helpful to the opponent in most cases. So when you have an exceptionally bad hitter, like a pitcher, it’s fine. But don’t bunt with guys who hit professionally.

For the most part, Fredi Gonzalez didn’t. Here’s how his teams ranked in terms of non-pitcher sacrifice attempts:

2011: 8th in the NL

2012: 13th

2013: 10th

2014: 11th

2015: 8th

2016: 2nd

2016 is the clear outlier, but 2016 has been a desperate year with a team filled with some exceptionally bad hitters, so I’m not going to hold it against him. He’s throwing things at the wall. In other years, though, Gonzalez did a good job avoiding the trap of giving outs away. Gonzalez always claimed to read about statistical analysis and newer ways of thinking. I’m not sure if he really did or if he was just giving lip service to those that cared about it, but if he did, his minor usage of the sacrifice bunt from his position players was an example that he perhaps was paying attention.

Hit & Run

Similar to stolen bases, I’m not sure how much this helps or hurts, but it’s an aspect of strategy, so here’s how many swings the Braves took with runners in motion:

2011: 289 (28th MLB)

2012: 288 (22nd)

2013: 241 (28th)

2014: 273 (22nd)

2015: 243 (26th)

2016: 69 (15th)

Again, he preferred station to station ball except in 2016, when he became desperate for anything and tried the hit & run more often.

The Platoon Advantage

It’s no secret that Fredi Gonzalez is a big fan of the platoon advantage. Righties hit lefties, lefties hit righties, and pitchers should pitch to batters of the same-handedness. While that’s true in a general sense, Fredi seemed to make it a major factor in his decision making. How did he compare to league average?

2011: 56.1% (league average: 54.0%)

2012: 56.7% (55.2%)

2013: 45.8% (55.6%)

2014: 43.8% (54.7%)

2015: 54.5% (53.5%)

2016: 62.9% (52.1%)

Considering his reputation, he didn’t seem to fill out lineup cards with the platoon split solely in mind. When he had his best offensive team – 2013, he relied on it little. When that offensive core returned for 2014, he relied on it less. It was only in years of offensive paucity or desperation (read: 2016) where Gonzalez really tried to use the platoon advantage in a statistically meaningful way.

Pitcher Strategy

Pitch Counts

Fredi Gonzalez’s starting pitchers were both typically effective and well-rested. That’s a nice combination, and a difficult one for managers to reconcile. Usually effectiveness breeds overuse, but Gonzalez mostly did a nice job keeping his starters fresh. Here’s the average SP pitch count and how it ranked in the majors:

2011: 95.9 (19th)

2012: 93.3 (22nd)

2013: 95.3 (15th)

2014: 98.2 (5th)

2015: 93.3 (13th)

2016: 91.4 (24th)

Only 5 starters in a little over 5 years threw over 120 pitches in a game. 120 isn’t some magic number, but it’s safe to say that’s stressful territory for almost any pitcher. Gonzalez didn’t let it happen much.

Also, Gonzalez didn’t let himself get into trouble trusting his starters too much. The Braves enjoyed an excellent quality start retention rate during his years as manager (games where the pitcher achieved a quality start and left the game with the quality start in tact, as opposed to being left in to blow it). 95.3% of quality starts were handed over to the bullpen with the quality start in tact. Perhaps it was too quick a hook for some, but Fredi Gonzalez wasn’t going to be mistaken for Grady Little.

Intentional Walks

Intentional walks are somewhat like the sacrifice bunt – freely allowing a baserunner to reach base when he already wasn’t likely to reach is sub-optimal. Sure, if you get the double play, it’s gold. But you don’t always do that, and sometimes the IBB hurts more than if you’d just pitched to the guy to begin with. Again, back to that run expectancy grid. Add a baserunner to any situation, and the run likelihood never goes down. Early in a game, it’s probably fine to force a pitcher to the plate, but elsewhere, even if you had, say, the best defensive SS in the game, it’s not the best strategy. If Gonzalez was an eager saber-student on sac-bunt day, he was regrettably sick on intentional walk day.

2011: 73 (1st in MLB)

2012: 40 (8th)

2013: 35 (12th)

2014: 36 (11th)

2015: 45 (3rd)

2016: 15 (1st)

Fredi Gonzalez gave too many free bases to opposing players, and it’s an aspect of his management that won’t be missed.

Bullpen Management

One of the keys of bullpen management is knowing which relievers to give important innings to. With Baseball Prospectus’ Bullpen (Mis)Management tool, we can visualize it.

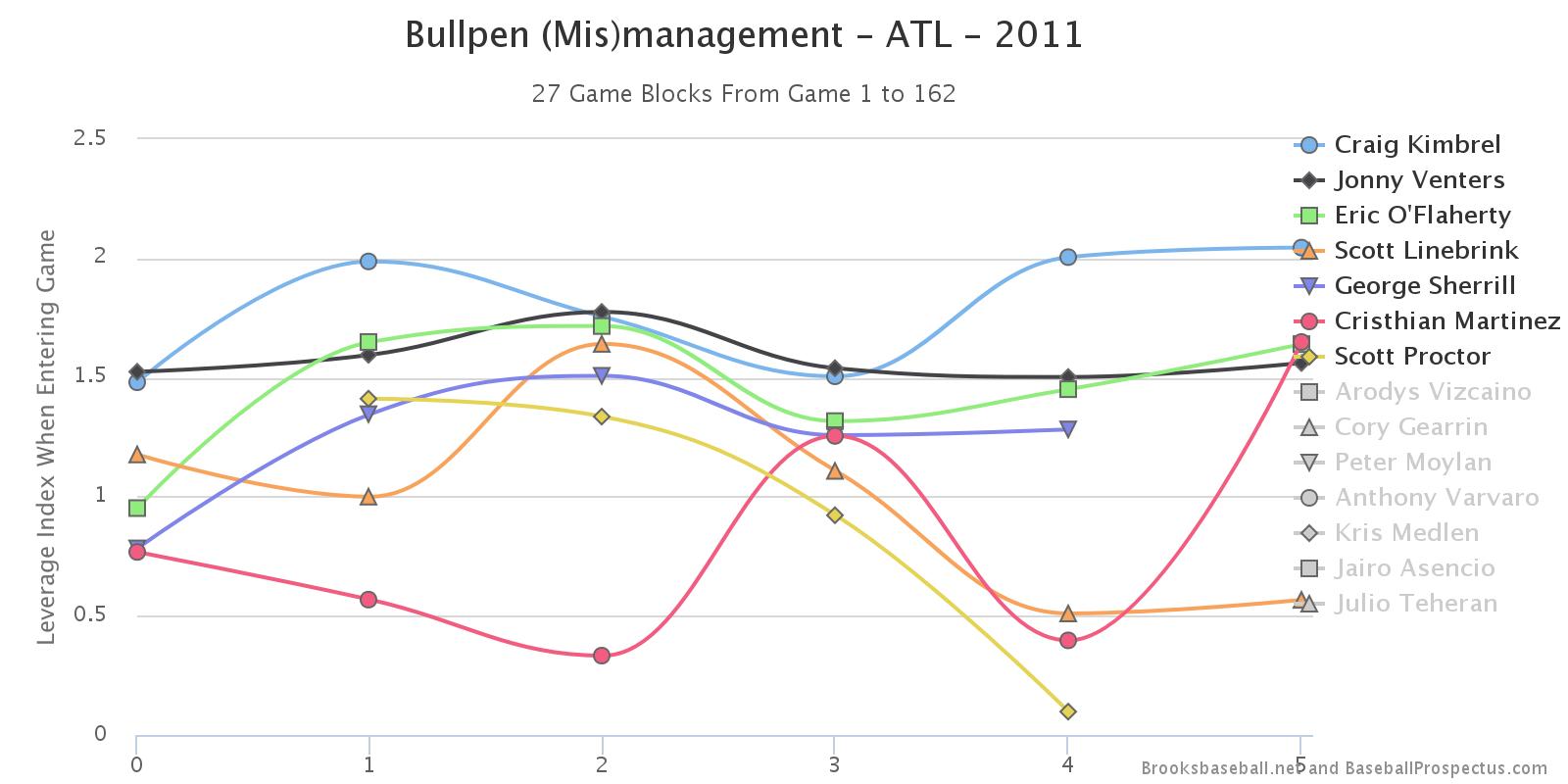

In 2011, Gonzalez finished the year strong. Rookie Craig Kimbrel was given the most important innings, although that might have been lucky since he was used as closer. Eric O’Flaherty and Jonny Venters were used in big spots. George Sherrill was used in less important situations. Scott Proctor (understandably) and Scott Linebrink (oddly) were given far less important roles as the year wore on, and Martinez was used as long men are used – for both unimportant mop-up duty and tie game multi-inning work. He was good enough to justify it.

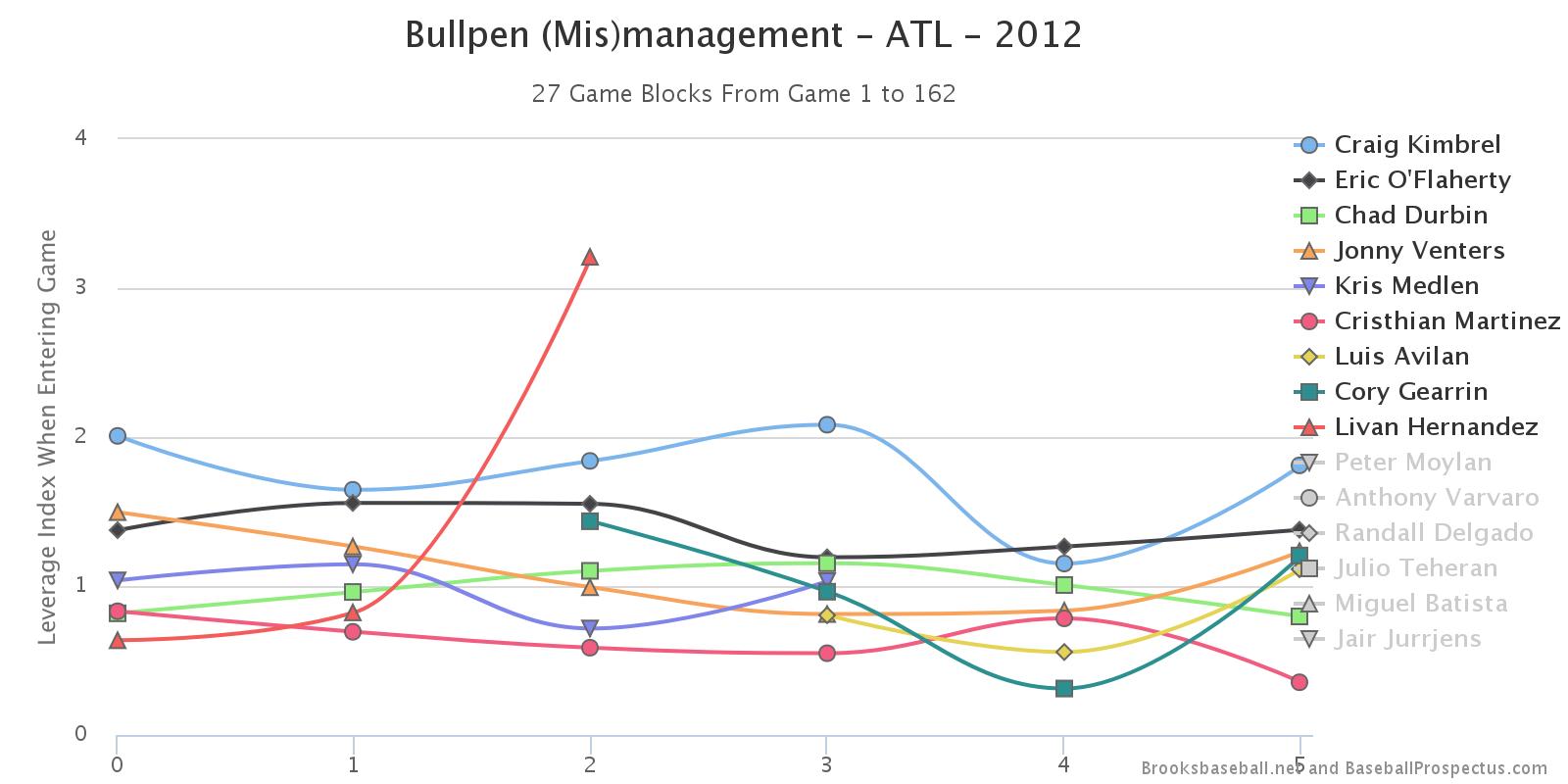

Again, Kimbrel rightly got the big innings, with O’Flaherty leading the secondary pitchers. Here we see a few of Gonzalez’ flaws. First, not being able to decide what to do with Cory Gearrin was odd. Second, a reluctance to give important innings to the outstanding Kris Medlen was disappointing. Most of all, phasing Christhian Martinez out of meaningful innings was an indication of Gonzalez’s reliance on ERA instead of the more predictive FIP.

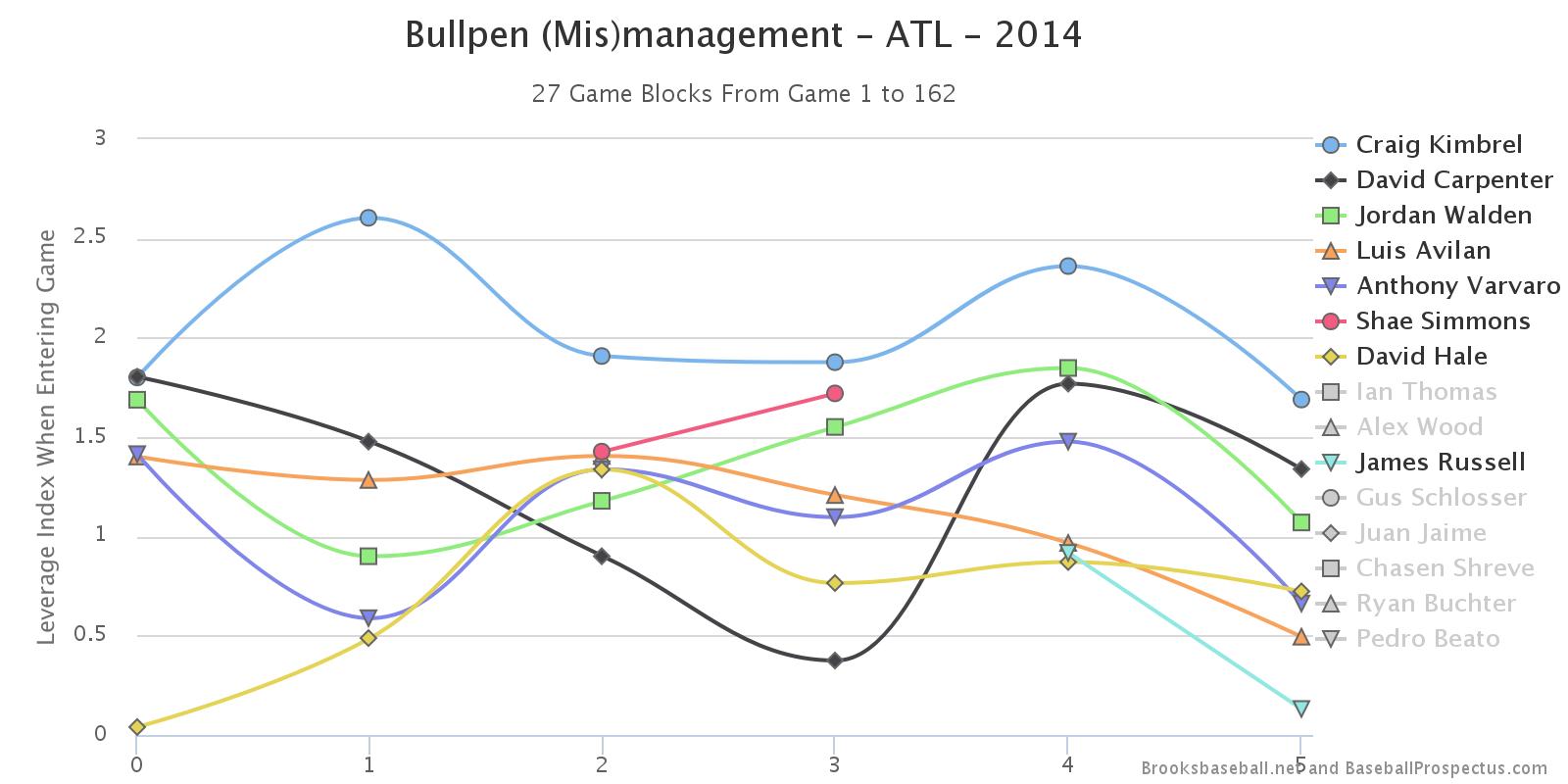

Warning: If you have blood pressure issues, do not view the next image.

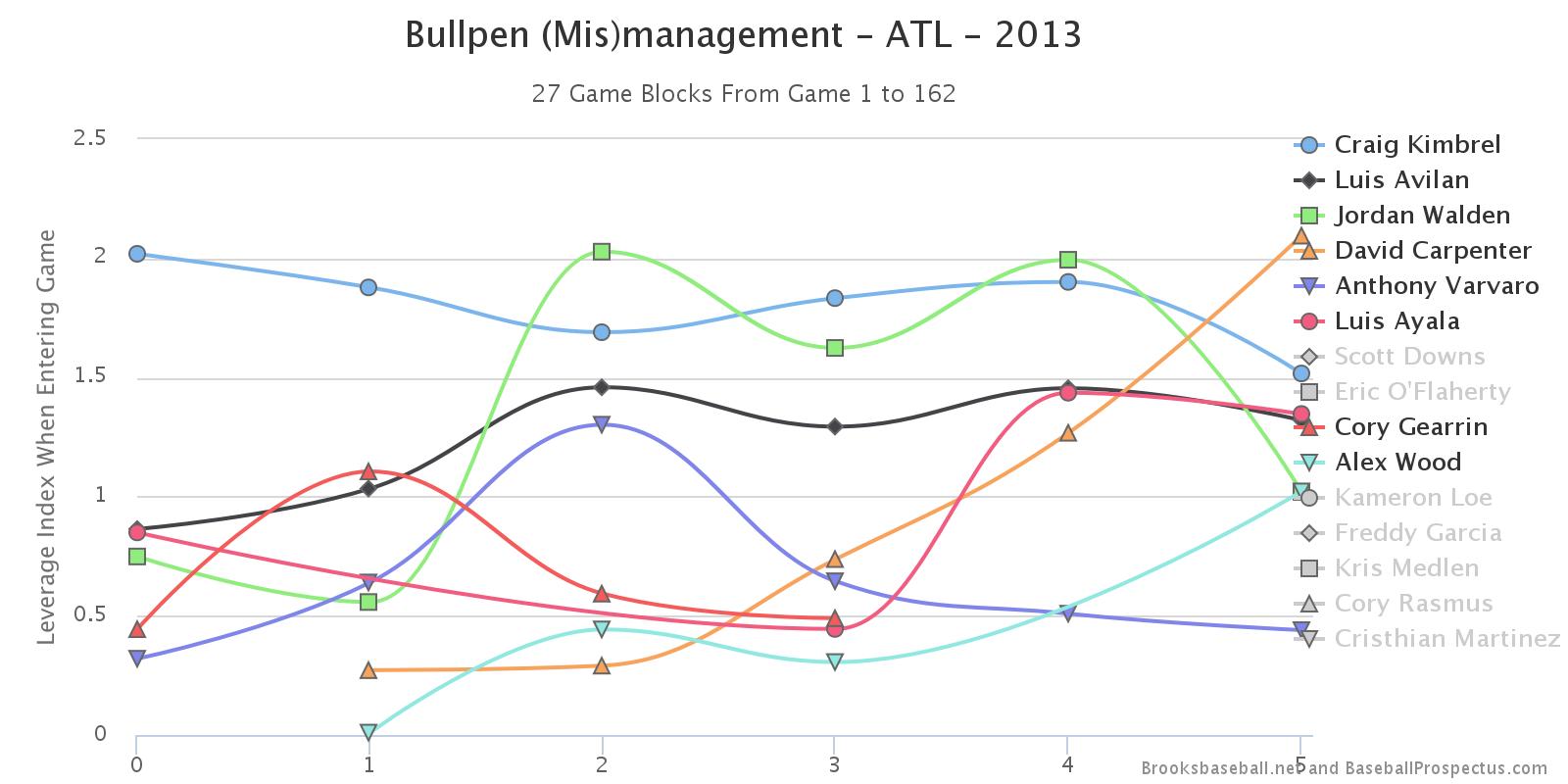

It’s painful because it reminds us, but it’s also just not very good. There’s the wild ride of Luis Ayala. There’s Anthony Varvaro, a league average-ish reliever, being put on the backburner. There’s Jordan Walden being used in more important situations than Craig Kimbrel, and then there’s the meteoric rise of David Carpenter.

Carpenter’s rise wasn’t without merits, but again, you have to be smarter than just glancing at ERA. Carpenter was basically on par with Walden that year, and both were excellent relievers. However, Gonzalez used Carpenter in increasingly important situations as the year wore on, and as Carpenter’s usage peaked in late September, the fanbase’s faith in Gonzalez hurtled toward its nadir.

You remember that night. I remember that night. I’m sure David Carpenter remembers that night. Juan Uribe sure as hell remembers that night. And Craig Kimbrel remembers that night. It will go down as the defining moment of Fredi Gonzalez’s tenure. In case you need a visual reminder:

Sorry about that, but you can’t take a look back at Fredi’s tenure without acknowledging the most indelible moment. It was the wrong call. It was one of the worst wrong calls in recent baseball history. I won’t go into the reasons it was bad in this piece, but suffice to say, it was bad. Fredi lost the support of many fans that day, and despite some improvements in the bullpen management area, he never really got them back.

In 2014, Gonzalez let Kimbrel reclaim his role as the ace reliever. Jordan Walden’s usage was kind of all over the place, despite being the second best reliever on staff. Fredi remained a slave to ERA – David Carpenter was still an effective reliever, but his usage in midseason was reserved for extremely low-leverage situations. Despite acquiring him at the trade deadline, Gonzalez was unwilling to use James Russell in bigger moments than Luis Avilan, and despite outperforming Avilan, Russell’s importance somehow dwindled as the year came to a close. It was a bit baffling, considering that Russell even had ERA on his side. And, as usual, Gonzalez couldn’t figure out what he wanted to do with Anthony Varvaro, who was again pretty effective.

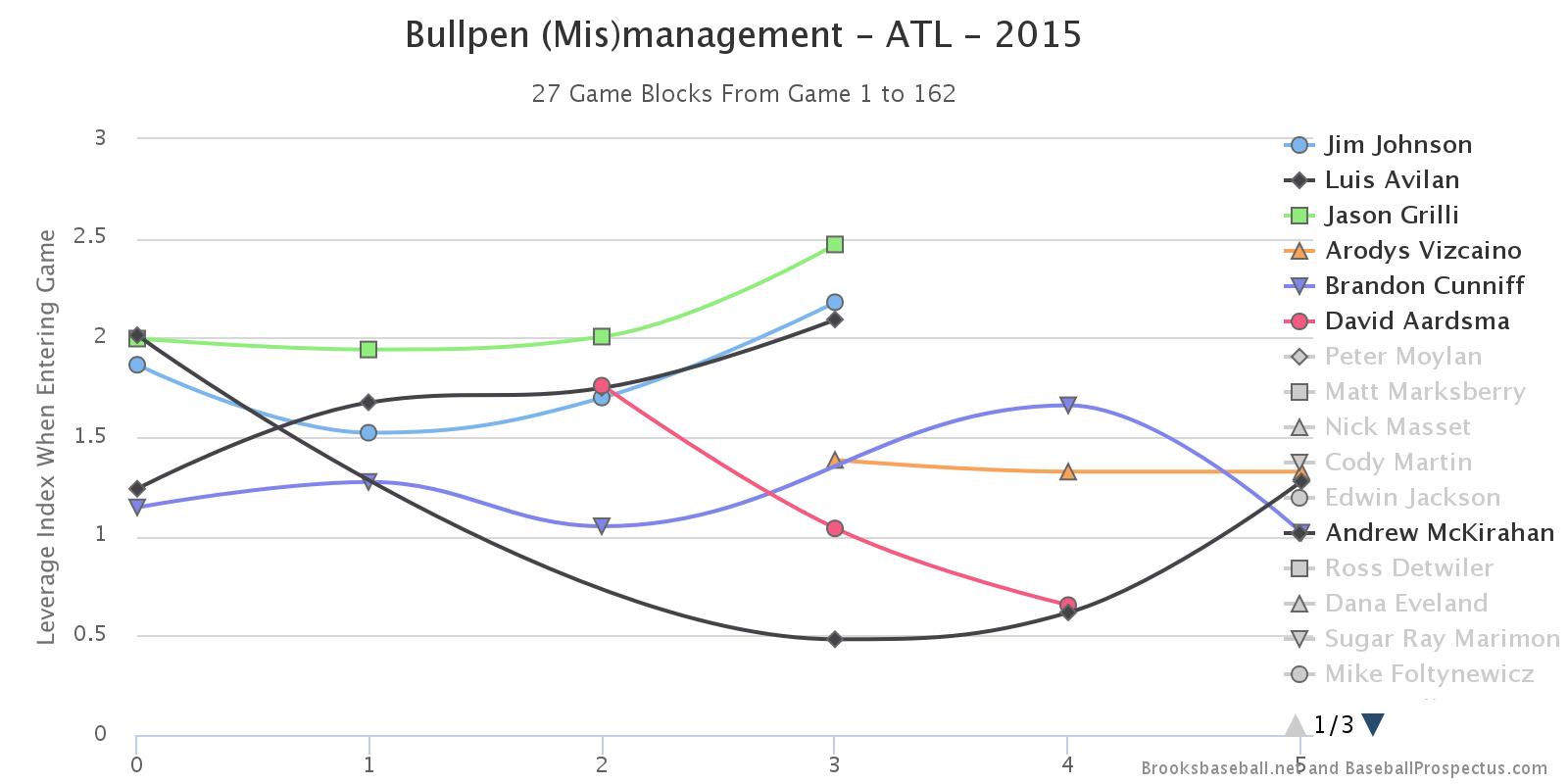

I’ve added the 2015 chart for posterity, but I don’t think there’s much to glean from it. Jason Grilli wound up injured for the season. Jim Johnson and Luis Avilan were traded. I suppose the only silliness was not giving Arodys Vizcaino the biggest innings in the second half, when Brandon Cunniff clearly wasn’t the answer. Also, starting David Aardsma off with such meaningful work when he hadn’t been an effective reliever since 2009 was a bit disconcerting. Still, Gonzalez’ 2015 bullpen dealt with a lot of turmoil and turnover, of which he was responsible for very little.

I won’t post the chart for 2016, as it has been a pretty small sample, but it would have been interesting to see over a full season, because Fredi Gonzalez had suddenly gotten pretty savvy with one facet of his bullpen usage: employing Arodys Vizcaino as a shutdown ace reliever without regard for inning. It’s pretty forward-thinking, and that’s not altogether surprising, considering Gonzalez’s biggest career error. From moments of self-realized idiocy, brilliance is sometimes born. Would another manager be as likely as Gonzalez to over-correct himself to the point where he starts using his best reliever in the most important situations? Few other managers have a single bad decision in reliever usage that hangs over them like a specter for their careers. Maybe the Carpenter-Kimbrel debacle is what led Gonzalez to using Vizcaino wisely in 2016. Granted, I think we’d trade a season of good bullpen management on a meaningless 2016 team for just one night of competence in 2013, but progress was made. It will be interesting to see if the next manager continues the trend.

The Platoon Advantage

When we looked at offensive strategy, we saw that Fredi’s adherence to righty-lefty matchups seemed limited to teams of his that were offensively weak. Was he the same when it came to pitching?

2011: 50.0% (league average: 46.0%)

2012: 43.8% (44.8%)

2013: 43.6% (44.4%)

2014: 44.7% (45.3%)

2015: 49.4% (46.5%)

2016: 62.7% (47.9%)

Here we see a bit more consistency. Aside from the desperation of 2016, Gonzalez generally was around league average with seeking righty-righty and lefty-lefty matchups on the mound. Again, it’s a reputation he earned, but I’m not sure he was unique enough to deserve it. It’s a common baseball strategy.

Reliever Rest

A common complaint of Fredi that surfaced several years ago was his perceived overworking of relievers. When Jonny Venters and Eric O’Flaherty (and later David Carpenter) declined a bit, people blamed Gonzalez for using them too much. Here’s the % of reliever appearances that came on 0 or 1 days of rest:

2011: 49.9% (48.2% league average)

2012: 50.7% (49.7%)

2013: 46.9% (48.1%)

2014: 49.4% (48.7%)

2015: 50.4% (48.8%)

2016: 39.2%

His reputation seemed to be somewhat well-earned. Only in 2013 did he preserve reliever rest at a rate better than league average. Is it coincidence that 2013 was the year Atlanta had the best bullpen in baseball? Probably, to an extent, but it’s at least notable. Gonzalez didn’t work his relievers drastically more than other managers, but he did tax them at a consistently higher than average level.

Defensive Shifts

It’s no secret that Atlanta is no organizational fan of shifting. Here’s how often the Braves employed a shift by year, and where it ranked in MLB:

2011: 114 (8th)

2012: 102 (25th)

2013: 157 (23rd)

2014: 254 (27th)

2015: 470 (29th)

2016: 310 (11th)

First, you can really see how the game has changed defensively since Fredi Gonzalez first came on the scene. 114 shifts in 2011 was good for 8th in MLB. More than 4 times as many were used in 2015, and the Braves were second-to-last. The Braves, as you can see, have certainly increased their use of the shift under Gonzalez, but not at a rate proportional to the league-wide increase in shifting. Despite growing usage, the Braves slipped in the league-wide standings. The 2016 team seems to be very shift-happy, but that could be statistical noise given the small sample size.

When Atlanta chooses its manager of the future, I hope he’s more willing to utilize shifts than Fredi Gonzalez was. And maybe this has more to do with an organizational philosophy than managerial philosophy, but suffice to say, Atlanta is under-utilizing a proven, effective method of helping its pitchers. Whether that change happens organization-wide or when the next full-time manager is hired, I hope it happens.

Farewell, Frediball

Fredi Gonzalez never seemed comfortable in his era. He talked about his willingness to be “new school” while he employed old school strategies and philosophies. He once said you “can’t use your closer in a tie game on the road”, and several years later had one of the most enlightened approaches to using his best reliever in the modern era. He routinely batted the pitcher 8th, but I’m not entirely sure he did so for the right reasons, if he had reasons at all. Batting the pitcher 8th is a “new school” philosophy, but it’s part of a bigger idea of lineup construction, a bigger idea (moving your best hitters to the top of the order) that he never fully embraced. Batting the pitcher 8th shows a willingness to think forwardly, but batting the pitcher 8th on its own achieves very little. Again, Gonzalez’s decisions always seemed to be in conflict with one another. It was better than blind stubbornness to adhering to the way his forerunners did it, but at the same time, it was a poor substitute for real progress. I think Gonzalez simply saw two sides of an argument, and he wanted to win over both sides. In the end, he won over neither.

All in all, he wasn’t an awful manager. I think it’s easy for Braves fans to misdiagnose him as awful, when there are some who are drastically worse at the major elements of management. However, he wasn’t a good manager, either. He didn’t inspire a lot of confidence with his decision-making or his leadership, and confidence is something the team really needs right now. I’m not sure what the future holds for Atlanta’s managerial position, but here’s hoping I at least know where the next guy stands.

Leave a Reply