Wanting your team to win day in and day out is at the heart of being a fan. That’s true across fan bases, across sports, across eras.

But winning is not only about the game that day, winning is about building a winning record to make the playoffs to compete for the title. When the calendar turns to September, some MLB fans are caught up in the excitement of the stretch run, but others already know their teams aren’t heading to the postseason.

What is This “Lose” of Which You Speak?

Maybe some are fans of baseball teams that tend toward losing, who are used to playing out the string. But for me, a fan of a hopeless and hapless Atlanta Braves team caught in the middle of the dreaded rebuild, I find myself unsure of what to do right now. The Braves have a long history of winning, of being in the thick of the race. This “losing” thing has me in unfamiliar territory.

I vaguely remember the late 1980’s, going to Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium and having my pick of the seats in a virtually empty stadium. But those memories are faint; a lot of winning has happened between my freshmen year in high school in 1991 and my two degrees, two careers, 12 years of marriage, and four children, the oldest of whom is too quickly approaching high school herself (She’s almost 11, but the day is coming!). Those days of being the most televised losers were a full generation ago. Many now-grown Atlanta Braves fans don’t even remember “those days” because THEY WEREN’T EVEN BORN!

From that worst to first season in 1991 to the team that won 97 games in 2013, the Braves went to the playoffs 17 times in 22 years (excluding the strike shortened 1994 season).

Sure, the Braves haven’t done well in the playoffs since the last World Series appearance in 1999 – winning only one playoff series way back in 2001 – but compared to a team like the Washington Nationals/Montreal Expos, who have NEVER won a playoff series, we’ve had it pretty good.

Sure, there are the Septembers of 2011 and 2014 haunting us, but the agony of collapse wasn’t known on September 1. No, the Braves were in the hunt on that day. The Braves are always in the hunt down the stretch – until this year.

I have grown accustomed to the excitement that comes with the turning of the calendar. In fact, in those 23 years since the Braves started their historically fan-spoiling run of division titles, only in 2008 were they completely out of it when September began – until this year.

In 2015, the Braves sat 19 games out of the playoffs with 31 to play as the calendar turned. There was not hope even for the most optimistic fan. Saying, “Today, I want my team to win,” rings a little more hollow under these circumstances. In fact, the more common statement heard ’round the virtual water cooler is, “Do we still have to play today? Can’t we just forfeit the season?”

After losing nine of the last ten August games – including two of three to the lowly Rockies before getting embarrassed by the Yankees in a home sweep that sounded more like it happened in New York followed by Shelby Miller closing a dreadful August by pitching well in yet another stellar loss (and single-handedly trying to prove win/loss records are meaningless) – forfeiting seemed a reasonable alternative to watching the September train wreck.

The fans do have a few options of how to respond to the misery:

- A common fan response is apathy. They might check in on the Braves occasionally, but for the most part they have checked out on baseball completely. Football season has now begun in the south in earnest, after all.

- Some fans, who are more noble (or stubborn) than I, cheer for the team to win day in and day out no matter how unlikely (or pointless) a victory is. There is nothing wrong with being this fan, but it sure is tough to maintain that kind of spirit after watching the beating the team took in August.

- The loudest fans are those bemoaning the state of the team, complaining about the front office, the manager, the players, the bat boys, and the hot dogs. They way this group talks, you might think there won’t even be a team in Atlanta in a couple of years.

[sc:InContentAd ]

The Better Option: Winning the Losing Game

The last option is to cheer for my team to lose. This clearly flies in the face of my opening statement. If the essence of a fan is to cheer for my team to win each day, then how can I both be a fan and cheer for my team to lose?

The answer is to shift your perspective. In fact, it might be better stated as turning perspective upside down. Instead of looking at the season as a means to the end of making the playoffs, a fan of a team completely out of it can look at the season as a means to the end of building for the future. The best way to do that is through the draft. Because Major League Baseball specifies the draft order is determined by reversing the season standings from the prior year (with worst record picking first and best record picking last) it is possible to win a better pick in the draft next year by losing on the field this year.

To turn perspective upside down, we need simply to flip the standings upside down. Now, instead of seeing the Braves slide down the standings with each humiliating loss, the Braves are currently climbing steadily in a very tight race for the top draft pick, possibly the next Chipper Jones, Bryce Harper, or David Price.

Just a few weeks ago, it looked like the Phillies had the number one pick in the 2016 draft locked down, but now the Braves are only 1 game out with a lot of teams right behind their current position of second pick [Note: table and paragraph updated to include games played Sept. 5]. My excitement in the season is renewed by following the “reverse standings”:

| GB | W | L | L10 | WP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Philadelphia Phillies | --- | 53 | 83 | 3-7 | 0.390 |

| 2 | Atlanta Braves | 1.0 | 54 | 82 | 0-10 | 0.397 |

| 3 | Cininnati Reds | 3.0 | 55 | 79 | 3-7 | 0.410 |

| 4 | Miami Marlins | 3.0 | 56 | 80 | 5-5 | 0.412 |

| 5 | Colorado Rockies | 3.5 | 56 | 79 | 5-5 | 0.415 |

| 6 | Oakland Athletics | 5.0 | 58 | 78 | 3-7 | 0.426 |

| 7 | Milwaukee Brewers | 7.5 | 60 | 75 | 7-3 | 0.444 |

| 8 | Detroit Tigers | 9.5 | 62 | 73 | 3-7 | 0.459 |

| 9 | Boston Red Sox | 10.5 | 63 | 72 | 6-4 | 0.467 |

| 10 | San Diego Padres | 12.0 | 65 | 71 | 3-7 | 0.478 |

| 11 | Seattle Mariners | 12.0 | 65 | 71 | 7-3 | 0.478 |

| 12 | Arizona Diamondbacks | 12.0 | 65 | 71 | 3-7 | 0.478 |

| 13 | Chicago White Sox | 12.0 | 64 | 70 | 5-5 | 0.478 |

If in doubt of this upside down perspective, just think back to the last time the Atlanta Braves finished last and secured the first pick in the draft. The year was 1989, and the first pick in 1990 was this guy:

For full disclosure, I am now actively rooting for my team to win the best draft pick next June. I want a shot at the next Chipper Jones, or even the Atlanta Braves only other first round pick, Bob Horner. It is the only thing that still matters. Therefore, it is what I will spend my September cheering for (along with the Georgia Bulldogs and their starting quarterback…well, we have Nick Chubb.)

Why a High MLB Draft Pick Matters

Protected Picks

Landing in the top 10 in the MLB Amateur Draft matters because these slots are protected picks. If a team makes a qualifying offer to a pending, eligible free agent, and the player turns it down, any team that signs the player forfeits its first round pick as compensation to the team who lost the player. (Note: the team losing the free agent doesn’t get that actual pick, but another pick between the first and second round). However, if the signing team has a top 10 pick, it is protected. It cannot be forfeited for signing a free agent with a qualifying offer. Instead, the team’s next pick is forfeited. As we will see below, there is a significant difference between losing a top 10 pick and losing a pick in the 20s.

For example, last year, the Braves made a qualifying offer to Ervin Santana. Had he accepted it, the Braves would have owed him $13.3 million for one year. Because he declined it, the Braves received the 28th pick (second compensation pick at the end of the first round) in the 2015 draft when the Twins signed Santana. The Braves used that pick to select Mike Soroka. The Twins had the sixth pick in the 2015 draft, so they did not have to forfeit it, and they used it to sign LHP Tyler Jay. They instead forfeited their second round pick. They likely would not have signed Santana if it meant forfeiting that top pick.

I have wondered if the 41st (currently) pick in the 2016 draft the Braves picked up from the Marlins in the trade of Alex Wood and Jose Peraza for Hector Olivera (and others) might be forfeited for signing a free agent this offseason. There are very mixed opinions of how active the Braves will be this winter, and how much they are willing to spend, but if nothing else, having a protected pick increases the Braves flexibility to pursue top free agents without fear of losing their best pick in the draft. As of now, the Braves are in very good shape to have a protected pick.

The highest pick increase the odds of getting an impact player

Most importantly, the top picks are more likely to develop into future impact players. I have seen some fans say the draft is a “crapshoot” and “blind luck” because there are so many minor leaguers drafted who never make it to the Major Leagues. If you look at all the 2015 picks from first pick Dansby Swanson to 1,215th pick Jacob McDavid, then only a very small percentage will ever make it to the majors. But scouting is not a mirage; teams do a pretty good job of evaluating talent and select the majority of it at the top of the draft.

A Visual Study on the Importance of a Top Draft Pick

To illustrate the importance of picking high in the draft, I analyzed each of the first 50 picks across June drafts from 1986 through 2005 (Interesting note, there were actually two amateur drafts annually from the first amateur draft in 1965 until 1986, when the January draft was eliminated.) I selected these years for two reasons:

- going back 20 years provides a reasonable number of players for each draft slot in order to gauge success of the players selected by slot

- stopping at the 2005 draft provides enough time for players to develop into a known major league quantity by 2015, even if some are still active

Some more analytical studies have been done to determine draft pick success by slot (such as this well designed study by Michael Jimenez), but I wanted a more visually understandable representation rather than a research project that led to more complicated results. To get at it, I used baseball-reference’s draft pick tool and analyzed “success” based on tiers of career bWAR.

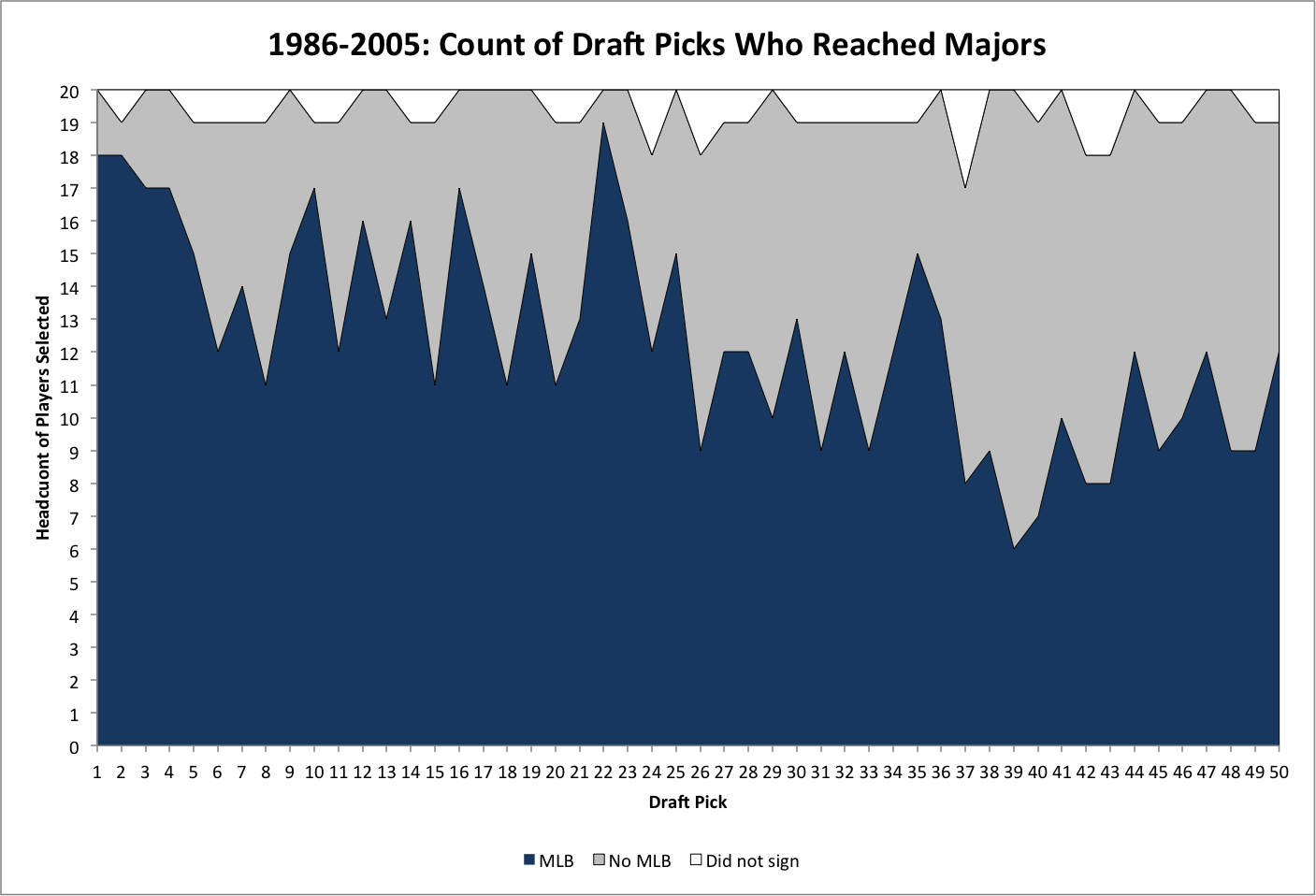

The first chart simply defines success by whether or not the player drafted in each slot made the Majors:

As you can see, the blue represents players who made the majors, and it encompasses the majority of the area. In fact, of the 965 signed players, 620 went on to play in the majors, a whopping 64% of the top 50 picks from 1986-2005. That is much more than a crapshoot.

Breaking down the chart further into percentage of signed picks making the majors:

- Picks 1-10: 79%

- Picks 11-20:69%

- Picks 21-30: 68%

- Picks 31-40: 52%

- Picks 41-50: 52%

There are a number of peaks and valleys as the data has a lot of variance when looking at each individual slot, but by grouping the picks, we can more easily see there is a an overall trend downward from pick one to pick 50 within that variability. Still, even from picks 41 to 50, teams have a better than 50% chance of a player making an appearance in the major leagues.

[sc:InContentAd ]Digging Below the Surface

However, there is a problem with defining success simply based on whether a player makes an appearance in the major leagues. There is a big difference in quality from the 49th pick in the 2003 draft and the 49th pick in the 1995 draft. The first is Abe Alvarez, who gave up 13 runs across 10.1 innings for a -0.4 bWAR. The second is Carlos Beltran, rookie of the year in 1999 and an eight-time all star selection who has accumulated 68.3 bWAR across his 17 year career.

So to account for these differences in quality of player making the major leagues, and without overly complicating the data, I broke up players into the following categories:

- -bWAR = accumulated a negative bWAR in MLB.

- +bWAR = accumulated a positive bWAR of less than 10 in MLB. This is a mix of players with very short, forgotten careers that happened to result in a small positive WAR, to useful players that flamed out quickly or had limited skill sets. For example, Braden Looper, the third pick in 1996, was a nice piece in the bullpen for eight years, even developing into a mostly effectively closer the last three of those years before turning into a starter for three more years. It’s a neat story, but he was never that valuable as a reliever and back-of-the-rotation starter and only amassed 7.2 bWAR in 11 years.

- +10 bWAR = accumulated between 10 and 30 bWAR in MLB. These players were regular contributors for a number of years, or stars that didn’t have longevity. For example, the 10th pick in 1999, Ben Sheets had the makings of a great pitcher, but injuries and inconsistencies held him back. He still amassed a 26.1 bWAR in his career. The 14th pick in 1994, Jason Varitek was an important piece for Boston for 14 years, but only had a couple of seasons where he put up really good numbers, never topping a 4.0 bWAR in a season. Still, over his career, he put up 24.3 bWAR.

- +30bWAR = accumulate 30 or more bWAR in MLB. These are the standout players who had to perform for a number of years at a high level, including a lot of superstars. These go from your Andy Benes type players who managed to stay healthy long enough and pitch effectively enough to accumulate 31.4 bWAR across 14 seasons as a starter, to Alex Rodriguez. Whatever you think of him, he has put up monster numbers for many years and accumulated 118.6 bWAR.

The categories are not intended to be perfect (no, there isn’t a big difference in an Andy Benes and a Jason Varitek), but they do provide a good way to visualize tiers of players in terms of quality of contribution and not just whether or not they ever made The Show.

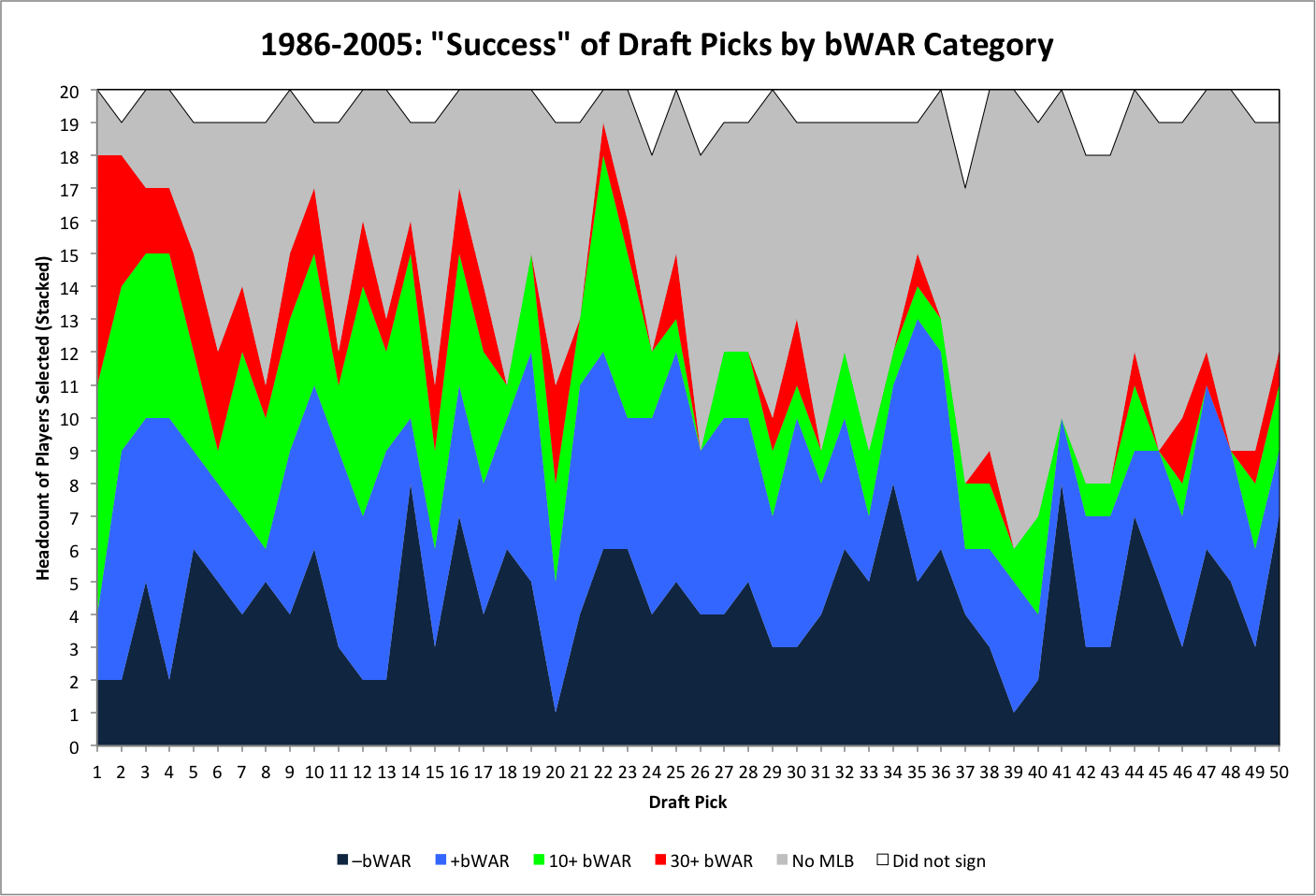

The second chart is the result of taking the chart above and breaking the players into the quality tiers:

There is a lot happening here in the stacked chart, but it makes sense.

The bottom tier of dark blue consist of players who had zero or negative impact in the majors based on having a bWAR of zero or less. These players clearly shouldn’t count as “successful” picks, yet they are accounting for 23% of the total in the first chart. Excluding these duds drops the number of players who “successfully” reached the MLB from 64% to 41%.

The lighter blue area consist of players who put up at least a 0.1 bWAR, but did not reach 10 bWAR. Now, that is not much, but there are plenty of players who have value to their team as role players in platoons, middle relievers, and so on who never quite reach 10 bWAR for one reason or another. Still, this doesn’t cut it for my purpose. When my team is in the bottom tier of teams because they are that bad, I want them to find an impact player who can help push the team over the top, not a role player who can serve admirably as a fourth outfielder. While I don’t consider this type of player a “bust,” it is at least a let-down in the first round. This group of let downs accounts for 22% of the total “successful” picks from the first chart.

So after redefining “success” of a draft pick as players who made the majors and accumulated at least 10 bWAR (green and red), only 19% of the players selected in the first 50 picks still qualify. I will refer to these players as “impact” players, or players who should at least be regular starters at the major league level.

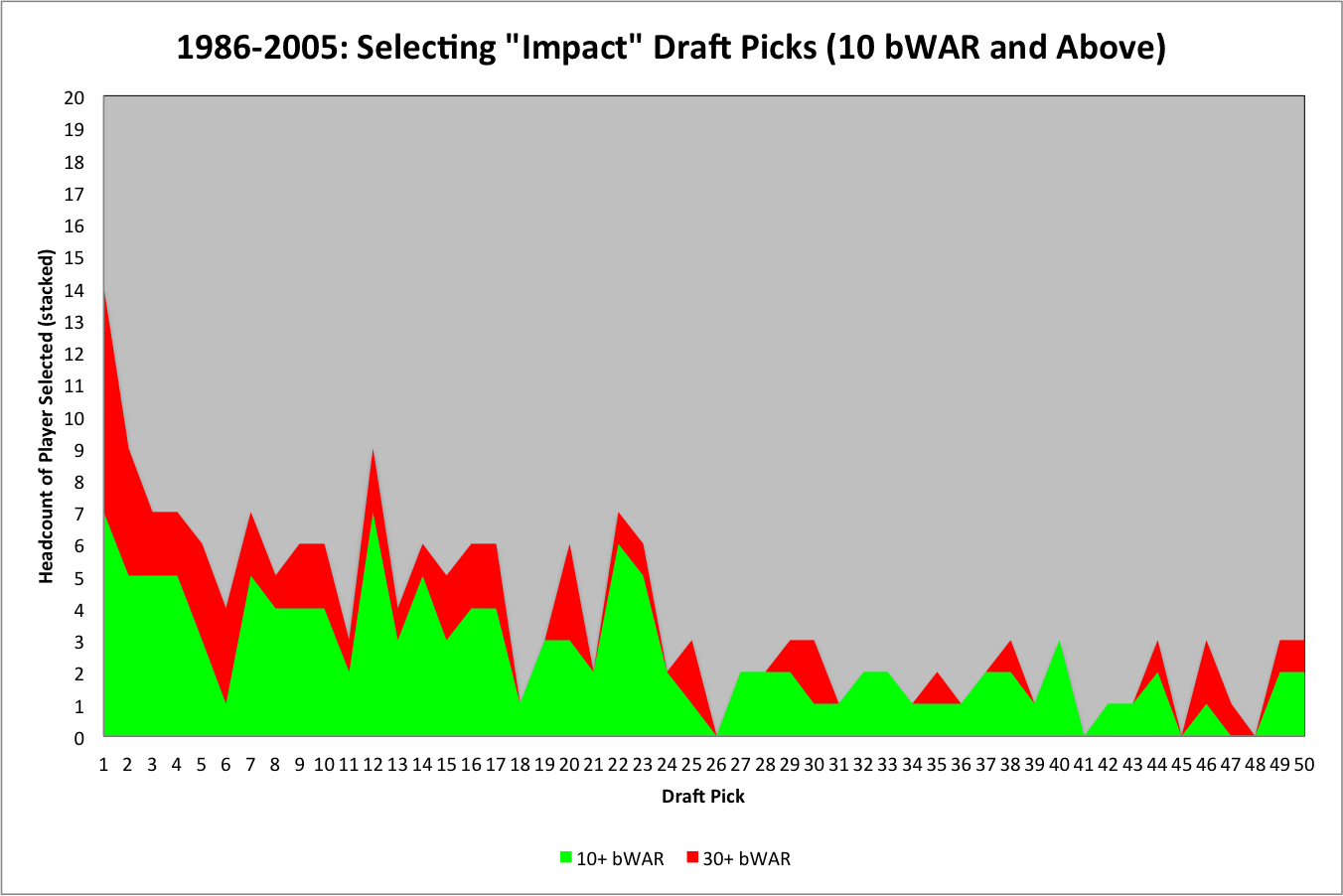

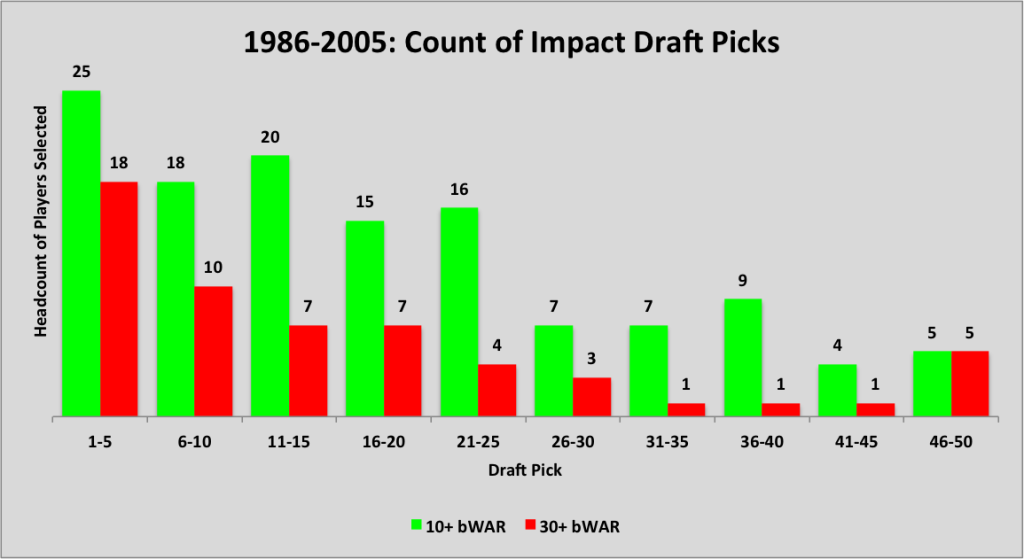

In the final chart, we have whittled down a “successful” pick to the final two groups composed of impact players:

The area covered is now much smaller, and leans much more heavily toward the top of the draft. Of the 965 signed picks from slot 1 through 50 over the last 20 years, 126 players (13%) accumulated between 10 bWAR and 30 bWAR. Just 57 players (6%) accumulated 30 or more bWAR.

Practical Impact

Now as a fan of the Braves, this is where it gets really interesting. If I want my team to get a high impact player, then I really, REALLY want that top pick. In the top slot, there is a 14 in 20 chance (70%) of getting a player who will be worth at least 10 bWAR, and a 7 in 20 chance (35%) of getting a player worth at least 30 bWAR. Compared to the overall odds of getting an impact player in the first 50 picks (19% and 6% respectively), that is a much, MUCH higher probability for success.

Impact Top 5 Picks:

| Draft Slot | Count +10 bWAR | Count +30 bWAR | Total Count | Percent +10 bWAR | Percent +30bWAR | Total Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 7 | 14 | 35% | 35% | 70% |

| 2 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 25% | 20% | 45% |

| 3 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 25% | 10% | 35% |

| 4 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 25% | 10% | 35% |

| 5 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 15% | 15% | 30% |

The probability of selecting an impact player drops quite a bit from the first pick to the second pick. The chance of drafting an impact player with the second pick is 9/20 (45%) and the chance of getting a 30+ bWAR player is only 4/20 (20%).

The odds only continue to fall from there. By the third pick in the draft, the likelihood of getting an impact player has fallen to half of what it was for the first pick. The odds of getting a game changer drops from 1-in-3 to 1-in-10.

The conclusion: The first pick matters. The second pick matters less, but is still more valuable than the next picks because of the greater likelihood of the +30 bWAR player.

Looking at the rest of the first 50 picks in groups of five helps to see the importance of these first picks in the greater context:

I hope the chart speaks for itself. In terms of +30 bWAR players, there is a distinct drop from the first five to the next five, and it continues steadily down after that (with an odd blip in picks 46-50). This tells me two things:

- You want to be in the Top 5.

- You have a shot at an impact player throughout the first 50 picks, and that’s why teams love to collect high draft picks, but are also more willing to sacrifice them the further away they get from the top 10.

In terms of +10 bWAR players, after the drop following the first 5 picks (once again, you really want one of those), there is a little more steady plateau, but a precipitous drop after the 21-25 group (and really after pick 23).

So, if you, like me, are convinced that it is worth flipping the standings and looking at the reverse standings, here is a summary of what to cheer for: You want your team to lock down a top five pick, really go for winning that top pick, but be happy settling for the second pick as a valuable consolation prize.

No I’m Not ACTUALLY Cheering Against My Team

I have one important final thought for anyone who can’t stomach the idea of cheering to lose because it is tantamount to the players trying to lose on purpose.

- I have no control over what the players do. My excitement at the Atlanta Braves moving into contention for the top draft spot in no way influences the players playing their heart out on the field.

- I WANT the players playing their heart out on the field. I recognize that the Braves are developing a lot of young talent, and filling gaps with old talent. I also recognize they simply aren’t good. We do not have much peak talent at the moment, especially with Andrelton Simmons and Freddie Freeman battling injuries (and still actually quite young). I am hoping the young players develop into +10 and +30bWAR players that show up on the chart in 10 years, but they are not there right now.

Really what I want to see is the best of both worlds. I want to see the young players take a step forward while playing their best, but I want them to do so while continuing to lose games, because that will also increase the future talent in an Atlanta Braves organization that has done a lot to improve it’s future…even if the results on the field really stink right now.

As a reds fan I flipped it up side done at the all star. Great story

Thank you. I’m glad I can do my small part to help several fan bases find hope in the misery.

Thank you. As a Brewers fan I had complete apathy towards the big Brewers-Reds showdown that I have pricey tickets for in a few weeks. Now I can see what might be at stake!

It’s confusing for teams at the bottom. You want to cheer when beating rivals, but come June, you don’t want them to have the pick ahead of you and take a great player. It would be nice to win these games, yet still get the better pick.

Having said that, I’m to the point with the Braves where I’m wanting them to lose to everyone. Mets, Phillies, Nationals, who cares. Why even win another game this season? Be so bad that it forces change for the better and secures the top pick.

Sometimes you have to hit rock bottom before you can make the change necessary to get help and get better. The Braves are about as close to rock bottom as a team can get, but philly is standing in the way of completing the fall….