Legendary Hall of Fame broadcaster Red Barber was once asked about whom he considered the most important figures in baseball history, and he responded: “Marvin Miller, along with Babe Ruth and Jackie Robinson, is one of the two or three most important men in baseball history.”

Babe Ruth? That’s easy, he was the best player during the first half of the 20th century and a legendary, larger-than-life figure.

Jackie Robinson? That’s also an easy one. He broke the color barrier and paved the way for thousands of ballplayers who would not have been able to play the game otherwise.

Marvin Miller? Why him? Wasn’t he just some union guy that presided over frequent player strikes?

Marvin Miller was so much more than that.

In 1966, MLB players had a union but it was pretty much in name only. The players were tied to their teams through what was called the “reserve clause”. This clause enabled the player’s team to reserve their rights on a season-to-season basis with players not moving teams unless they were released or traded, Because of this, players had no financial leverage and had settle for “take it or leave it” offers from management. The owners encountered resistance to the status quo when, after the Los Angeles Dodgers won the 1965 World Series, Don Drysdale and Sandy Koufax entered into joint negotiations with the Dodgers the following season to enhance their bargaining power. Facing the loss of 50% of their rotation, the Dodgers caved and signed Koufax for $125,000 and Drysdale for $110,000. At the time, they were the largest contracts in baseball history.

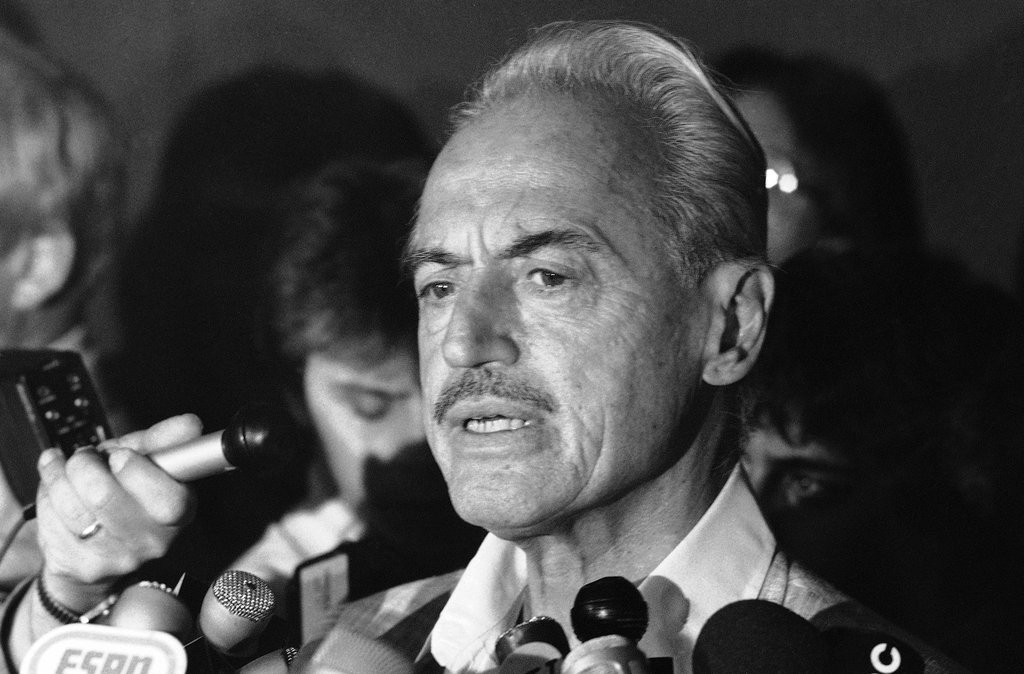

During that time, pitchers Jim Bunning and Robin Roberts, both of whom would later be elected to the Hall of Fame, asked Marvin Miller, who was employed as the chief economist and negotiator for the steelworkers union, to serve as the first-ever full-time director of the Major League Baseball Players Association.

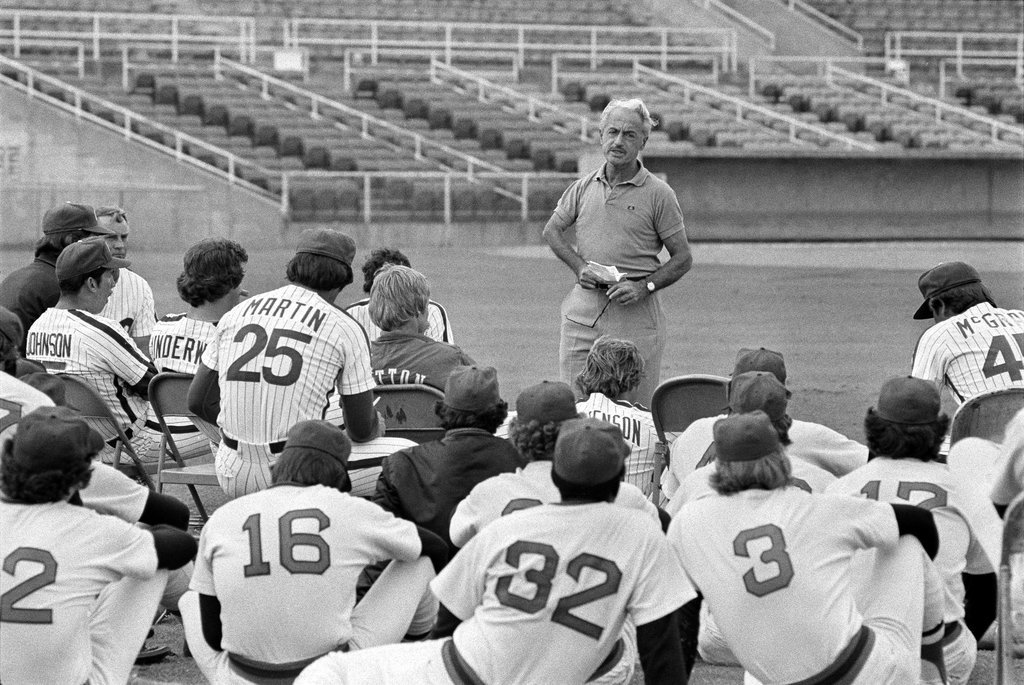

Many players, afraid of upsetting the owners, were resistant to the idea at first. Miller, in his first meetings with the players, challenged them: “If at any point the owners start singing my praises, there’s only one thing for you to do, and that’s fire me. And I’m not kidding.”

In 1968, Miller led the MLBPA negotiations to create the first-ever collective bargaining agreement. This wasn’t the first CBA only in baseball, but in all of professional sports. The primary achievement for the union in the initial CBA was to set the minimum player salary at $10,000. This was up from the $6,000 mark where it had remained since the 1940s.

A major milestone was achieved in the 1970s with the advent of arbitration to settle grievances. Further gains were attained in subsequent years including additional minimum salary increases, licensing rights, pension funds and increased revenues.

One of Marvin Miller’s greatest victories, however, was initially a loss.

At the conclusion of the 1969 season, outfielder Curt Flood was traded from the perpetual playoff-contending St. Louis Cardinals to the cellar-dwelling Philadelphia Phillies. Flood, citing the Phillies’ record, fan base and poor stadium, refused to report, risking his $100,000 contract. After consulting with Miller and with financial backing from the union, Flood decided to pursue a legal course of action.

Flood sent a letter to commissioner Bowie Kuhn demanding that he be declared a free agent, which was denied based on the reserve clause. On January 16th, 1970, Flood sued Kuhn and Major League Baseball for $1 million, citing violation of federal antitrust laws. The case was argued before the Supreme Court on March 20th with MLB’s argument being based on maintaining the best interests of the game while Flood’s case was centered on the reserve clause artificially holding down wages by limiting players to one team for their entire career. On June 19th, the court ruled in favor of Major League Baseball, citing that antitrust laws did not apply.

Although Flood lost his case, it brought public awareness and rallied players to band together to fight for this cause.

Later, the National Labor Relations Board reached the decision that baseball fell under its jurisdiction rather than the courts. This took the fight out of the courtroom and into arbitration where the Seitz decision regarding pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally prior to the 1976 season put an end to the reserve clause once and for all. Once appeals were exhausted, MLB and the MLBPA signed an agreement allowing players to become free agents after six years.

In today’s labor climate, the MLBPA needs someone like Marvin Miller to lead them into the future. It’s a good thing to have players involved; after all, players like David Cone and Tom Glavine were front and center during the 1994 strike. However, the MLBPA needs to be led by someone with a background in economics, a trained negotiator and armed with a bulldog mentality who is willing to take short-term losses for long-term benefits. They also need to be prepared to fight for the economic future of the players and not fighting over secondary perks like clubhouse chefs, extra spring training bus seats and additional off-days.

It has been said that the best result in a negotiation is one where neither party is completely happy. Major League Baseball owners seem to be awfully happy these days.

sorry, but unions are antiquated remnants of a bygone era. It is far more interested in pumping up declining player salaries than the younger guys (and totally ignore the minors) I tend to think that the union no longer serves a purpose and should be folded.

Who would fight the collusion and medical issues and salaries and scheduling problem to name just a few?

If you read my previous piece on the lack of pay and benefits for minor leaguers, that’s what can happen if you don’t have a union.

I was actually responding to jaysoos

Sorry, I was too. It appears not to have threaded correctly.