See also: Best Brave By Uniform Number Index

The best Brave to wear #27 is the greatest mid-season buyer’s acquisition in Braves history (that way you can’t argue for Smoltz in ’87). On July 17, 1993, the Braves dropped a 4-3 decision to the Pirates. It dropped the Braves to 52-40, certainly a record to be proud of, but somehow 9 games behind the Giants in the NL West, and only 4th in the NL (behind the Phillies and Cardinals as well). 1st baseman Sid Bream went 0-4, dropping his line to .239/.306/.395. His platoon partner, Brian Hunter, was faring even worse, hitting an awful .123/.141/.192. Something needed to jolt Atlanta back into the race, and hopefully get some production at first base.

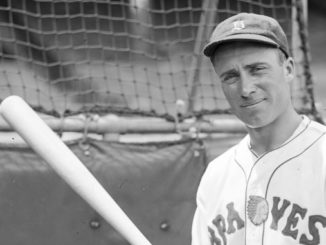

On July 18, the Braves traded Melvin Nieves (Baseball America’s #5 Braves prospect), Donnie Elliott (#9), and Vince Moore to the San Diego Padres for the man who would be the best Brave to wear #27 – the Crime Dog, Fred McGriff.

McGriff had been a star with the Blue Jays, winning a HR crown in 1989 and OBP-ing .400 in 1990. The Blue Jays jettisoned McGriff to San Diego to acquire Roberto Alomar and Joe Carter – a particularly justifiable move considering John Olerud was on hand to replace him. He led the NL in HR in 1992, topping 30 for the 5th straight season. The day of the trade, McGriff was slashing .275/.361/.497 with 18 HR. Another solid season, if maybe not as stellar as a few others.

As soon as McGriff arrived in Atlanta, he caught fire. And so did Atlanta Fulton County Stadium. Hours before McGriff’s scheduled debut, this happened:

Hours later, this happened:

The next night, McGriff hit 2 homers. He started a total of 6 games for Atlanta that year in which he failed to reach base. He hit .310/.392/.612 for Atlanta, led the team roaring back to an absurd 51-17 finish. Atlanta won 104 games and won the NL West by a single game. Amazingly, the Giants didn’t even really lose steam. After the McGriff trade, the Giants played at a .604 clip (97-65 pace). Handing a team a 9 game lead and then setting their win rate at 60% should pretty much guarantee a division title. Fred McGriff had other plans.

In 1994, McGriff was outstanding again – .318/.389/.623 with 34 homers. He also happened to provide the best moment of the entire season for me. I was 10 years old in the summer of ’94, and I subscribed to Baseball Weekly, USA Today’s MLB publication. I mostly liked it to follow transaction news, so I could re-shuffle my baseball cards to properly represent current teams, or maybe re-align the cards in Statis Pro Baseball, of which I owned the 1993 version. I liked the stat tables, especially during the era of offensive explosion. But I also skimmed the headlines, so even though I didn’t read the finer details of the labor strife, I understood what was happening. There was a dark cloud hanging over that summer. Even if you didn’t want to believe it, you could feel it. The strike was coming, and the World Series might be canceled.

In mid-July, when the AL met the NL in Pittsburgh for the All-Star Game, it wound up being a moment of catharsis for players and fans. First off, it had arguably the greatest Home Run Derby ever, and then it followed with the greatest All-Star game of my lifetime. That All-Star game was all we had. We knew it deep down. That was our season, even if the teams were going to keep playing like August 12 wasn’t just around the corner. This was our World Series. And having lost pretty much every All-Star game I had really cared about to that point, this one really mattered.

Greg Maddux, the starter, gave up a run, putting me in a sour mood. Dave Justice went 0-2. In the 6th, the NL surrendered its 4-1 lead (ruining Mad Dog’s shot at a win), and after retaking the lead in the bottom frame, gave up another 3 runs in the 7th to trail 7-5. That lead held into the 9th, when Lee Smith, the man on his way to the MLB saves record (since broken, of course) came in to close it out. He walked Marquis Grissom, and then Craig Biggio grounded to 3rd, forcing Grissom out at 2nd. With one out, and the pitcher’s spot due up, Atlanta’s Fred McGriff was called on to pinch-hit with the game on the line.

I jogged every step of the way with the Crime Dog, just leaping and running through my house at what felt like the early morning hours, simply because my folks had already gone to bed. They told me to quieten down, to which I responded, “McGriff tied it with a homer!” Mom didn’t care. I heard Dad exclaim, “All right!”

It was probably the purest moment of baseball-induced joy in my life. In 1991, I think I was just a little too young to fully appreciate it all. I followed it, but I had no real concept of baseball sadness. Hell, I had no concept of winning before that season – I just assumed all baseball fans attended games in nearly empty stadiums, not worrying about their seats and just finding a nice spot down near the field to sit. 1991 brought traffic and… lines. It was weird. Francisco Cabrera should have been a moment like that, but again, I just believed Atlanta was destined for greatness. It was so pre-ordained in my mind, it came as no surprise. When Atlanta lost to Toronto later that month, I started to get a little confused and began to realize the possibility that great things won’t automatically come to us.

After the summer of 1993, however, I was back to believing that we were destined, owed a World Championship. The 1993 NLCS crushed that, naturally. So, by the time the team won in 1995, it wasn’t so much joy for me as it was relief. I didn’t want to hitch my emotional wagon to a team that was never going to get it done. In 1995, there was joy, but it was mostly just an ability to exhale, knowing my team of the 90’s had shaken the “choke” label (1 – they hadn’t | 2 – it was a dumb label anyway used by dumb people to justify their dumbed down thought processes).

Anyway, 1994 was that sweet spot for me, and McGriff’s HR seemed to shoot me out of a cannon in my rural living room. It ended the following inning on a Moises Alou double, bringing Tony Gwynn home. McGriff’s homer was not in vain. We had won. The NL had won 1994. Fred McGriff had won 1994.

Crime Dog was solid in the championship season of 1995 (.280/.361/.489, 27 HR), and was again in 1996 (.295/.365/.494, 28 HR). 1997 saw a slight decline, and Atlanta opted to let McGriff head to Tampa, signing Andres Galarraga to take his place.

He would be beloved and productive in his home town, and would spend time with the Cubs and Dodgers before calling it quits after 2004. His HOF candidacy remains a topic of interest. I think he’d be in by now if not for ballot-bloating due to voters stonewalling steroid users. When half the voters are having to use a vote every year on, oh, the greatest hitter of our lifetimes, players like McGriff don’t get the dialogue they deserve.

Honorable Mentions:

- Lonnie Smith may best be remembered for his baserunning gaffe in the 1991 World Series, but he should probably instead be remembered for his 1989 season. On a terrible team, Smith had an All-Star caliber year, slashing .315/.415/.533 with 21 HR (his career high by a dozen) and 25 steals. He was quite good in 1990 as well.

- Pascual Perez is also remembered for a gaffe when it came to travel – his trip around, and around, and around I-285. But he was really good for a couple of years, earning a spot on the 1983 All-Star team and going 29-16 with a 3.58 ERA in ’83-’84.

Who is the best ever to wear #27?

As good as Vladimir Guerrero was, I’m taking the Dominican Dandy, Juan Marichal.

And Fred McGriff did it all without steroids !