With the nation and the world still in the grips of the COVID-19 pandemic and most sports shut down in the United States, including major and minor league baseball, the raison d’être for this blog has taken a hit. That said, we at Outfield Fly Rule salute the nurses, doctors, EMC personnel, and essential workers risking their lives and health to keep the nation going. The suspension of our sports passion is a small price to pay compared to the millions that have contracted this disease and the many more working hard to mitigate its future effects.

For this post, I have gone back through and tried to identify the best transaction made by every Braves general manager since the start of the franchise in Boston back in 1871, five years before the founding of the National League itself. Of course, back in 1871 the wasn’t called the Braves, a name that didn’t come into regular use for 41 more years, in 1912. Also in 1871 there wasn’t a position called “general manager”; the first person to hold that title with the organization was Bob Quinn in 1936. Nevertheless, I tried to identify the principle person who was making the major personnel decisions at the time.

Harry Wright, 1871-1881

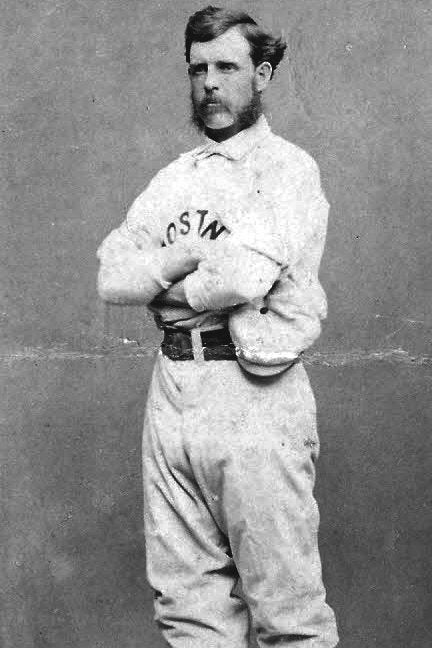

Harry Wright was pivotal in the early days of professional baseball. Wright was the player-manager of the first professional baseball team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, which started in 1869. Cincinnati de-certified after the 1870 season however, and Ivers Whitney Adams, head of the ownership group that created the Boston professional baseball club, hired Wright away in a move that ignited interest in the new club. Wright would manage the Boston Red Stockings, as the Braves were then known, for 11 seasons, the first five in the National Association and then in the brand new National League, winning eight titles, making the franchise the most dominant club of the 19th-century.

Adams and his group essentially left all baseball decisions to Wright, so for this period I am counting him as the “general manager”.

Best Transaction: acquisition of RHP Al Spalding (1871). Before the first game, Wright made a number of signings to fill out his brand new club. The most significant was signing 20-year-old Al Spalding from the amateur Rockford Forest Cities. On a team filled with 19th-century baseball legends like Jim O’Rourke, Deacon White, and Harry Wright’s Hall-of-Fame brother George Wright, Spalding was the lock-down starting pitcher, averaging 56 starts a season and accumulating 204 wins and a 2.21 ERA before becoming involved in the organization of the American League and jumping to the new Chicago White Stockings as player-manager. Spalding would only pitch two seasons for Chicago before he retired to become the team’s full-time president. He and his brother also started the sporting goods company that still bears their name.

Arthur Soden and the Triumvirs, 1882-1906

In 1877, Soden and his business partners J .B. Billings and William Conant acquired the controlling interest in the Boston franchise. While Billings and Conant were named the team’s treasurer and secretary respectively, Soden was the team president. For most of the early years of the ownership, Soden and his two partners, a group that fans started call “the Triumvirs”, allowed manager Harry Wright to continue to make most of the baseball decisions while they concentrated on sales, cost-controlling measures, and helping prop up the nascent National League, with Soden even serving as the league president temporarily after the death of National League founder William Hulbert. After two 6th-place seasons in 1880 and 1881 however, Wright left the team after conflicts with Soden regarding the many cost-cutting measures put in place by the Trumvirs, including having the team stay in sub-class hotels on road trips. Soden tapped first baseman John Morrill to be player-manager and the Triumvirs took a much bigger hand in the baseball operations side of the business.

It was Soden who lead other league owners to create a rule that allowed teams to “reserve” five players per squad to keep them from signing with other National League teams. This “reserve clause” was quickly expanded to the entire roster, creating a rule that would prevent player free agency without owner’s consent for nearly 80 years until, perhaps ironically, the Braves would sign pitcher Andy Messersmith as a free agent.

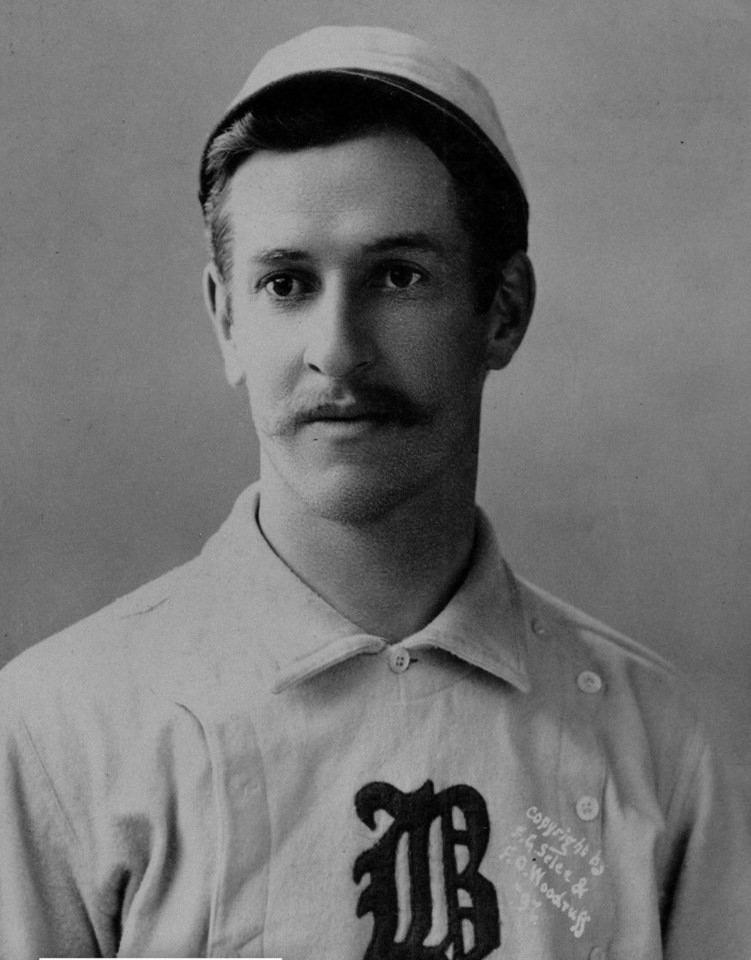

Best Transaction: hiring Frank Selee as manager and the acquisiton of RHP Kid Nichols (1890). The Boston club, now more commonly called “the Beaneaters” by the press, would only have one first-place finish in Morrill’s seven seasons at the helm, despite some highly-publicized transactions including the purchasing of superstars King Kelly and John Clarkson for $10,000 apiece from Chicago in consecutive seasons, a then-unheard of acquisition cost. For on-field results however, the most significant move was the hiring of Frank Selee as manager. Selee had been managing Omaha of the Western League (a precursor to the American League). Selee wanted to bring along his young star pitcher, 20-year-old Charles “Kid” Nichols. Nichols turned down offers from the Reds, Cubs, and Cardinals to stay with Selee. Nichols would go on to become the most dominating starting pitcher of the 19th-century, leading the Beaneaters to five first-place finishes in his 11 years with the club. Selee’s 1004 managerial wins would pace the Braves franchise until eventually passed by fellow Hall-of-Fame manager Bobby Cox.

The Boston franchise took a turn for the worse however as most of the talent that made the club a perennial favorite in the 1890s jumped ship to the American League, most of them to the new cross-town Boston Red Stockings, shortly after the turn of the century. The stingy ownership practices of the Triumvirs prevented them from challenging the exodus with counteroffers and they quickly found themselves the “other team” in town compared to the more talented American League team. With profits dwindling, J.B Billings sold out to Soden and Conant in 1904. By 1906, Soden and Conant found a buyer themselves.

John and George Dovey, 1907-1910

Fans and press were so happy that the stingy Triumvirs finally were no longer pulling the strings of the Beaneaters that they colloquially named the team after the new owners, brothers John and George Dovey, and the team became known as the Boston Doves. Unfortunately the club would fare no better in the four short years under Dovey control, finishing no better than 6th in the standings, going through five different managers in those four seasons. Sadly, tragedy struck the duo when George was killed by a pulmonary hemorrhage at the age of 46 while on a scouting trip in the midwest in 1909. While they shared ownership responsibilities, George was more invested in the baseball operations side of the business having been a former amateur player himself, while John was focused on the business administration side. With his brother gone, John Dovey sold his interest in the team after the 1910 season.

Best Transaction: traded UT Del Howard to the Chicago Cubs for IF Bill Sweeney and OF Newt Randall (1907). The best transaction consummated by the Doveys was also one of their first. Utilityman Del Howard was having a career year in 1907, hitting .273/.330/.332 for the Doves, a solid line in the dead-ball era. Young infielder Bill Sweeney was blocked from playing time by the legendary infielders Johnny Evers and Joe Tinker of the Cubs, so a swap was arranged. In seven seasons with Boston, Sweeney would go on to hit .280/.356/.354 and accumulate 12.6 fWAR, seventh most among Braves middle infielders in franchise history.

William Russell, 1911

Before the 1911 season, the franchise fell into the hands of William Russell and Lewis Cloues Page, with Russell acting as managing partner. A lawyer and former big-wig in New York politics, Russell found himself in ill health and felt that running a baseball team would be a good distraction that wouldn’t provide much stress. The press, after giving the team the name “Doves” after the previous owners, called the team the Boston Rustlers in Russell’s honor. Before a year was complete from the purchase however, the team would finish in 8th place and Russell would be dead.

Best Transaction: traded IF Buck Herzog to the New York Giants for C Hank Gowdy and SS Al Bridwell (1911). With the team foundering in the second division, Russell was able to convert half a good season of infielder Buck Herzog, who was hitting .310/.398/.459 at the time, into veteran shortstop Al Bridwell and young catcher Hank Gowdy. Bridwell was a short-term replacement for Herzog, but Gowdy would end up having a 14-season career with the Braves and have a pivotal role with the 1914 Miracle Braves, hitting .545/.688/1.273 for the Series and becoming the first (but not only) Braves player to earn the nickname “Hammerin’ Hank”. Gowdy also has the distinction of being the first major league player to enlist for World War I and was the only major league player to fight in both World War I and II.

James Gaffney, 1912

After his death, Russell’s estate sold controlling interest in the Boston franchise to New York construction mogul and Tammany Hall political machine big-wig James Gaffney. Gaffney had nearly no interest in the on-field play of the team, seeing the club as purely a business opportunity. To that end he partnered with former major league player John Montgomery Ward to act as club president. Gaffney and Ward also firmly took control of the team’s nickname away from the press and fans, announcing that the club would be called the Boston Braves, an homage to Chief Tamanend of the Delaware Native American tribes, for whom Tammany Hall was named.

It didn’t take long however for the two to come to disagreement about the running of the team, and Gaffney would end up buying out Ward before the 1912 season was even completed. At least one reason for the falling out was the best transaction made in 1912, when Gaffney overruled Ward.

Best Transaction: traded RHP Brad Hogg and $1000 to New Bedford (New England League) for SS Rabbit Maranville (1912). Maranville would go on to play parts of 23 seasons in the major leagues, 15 of them for the Braves in two separate stints. Widely regarded as the top defensive shortstop of his time, Maranville would end up in the Hall of Fame and finish in the top 3 in MVP voting in 1913 and 1914.

George Stallings, 1913-1920

Despite trading for Maranville and purchasing 20-year-old right-hander Bill James, who would be the star pitcher for the 1914 Miracle Braves, Gaffney still wanted someone else to handle the Braves’ baseball operations. After another 8th-place finish in 1912, Gaffney hired manager “Gentleman” George Stallings to not only helm the squad on the field, but to make most of the baseball operations decisions of the club. It was under the guidance of Stallings that the “Miracle” Braves won the World Series in 1914.

Gaffney would go on to be instrumental in the financing and construction of Braves Field, which opened in 1915 as the crowned jewel of National League ballparks of the time. When Gaffney sold the club after the 1915 season, he retained ownership of the ballpark, becoming the team’s landlord. Gaffney’s estate would continue to own Braves Field until 1949.

Stallings would continue to manage the club through the next ownership change, though 1915 was the last season the team finished above .500. Stallings would voluntarily leave after the 1920 season. Nine years later he would be hospitalized due to heart disease. According to legend, when his doctor asked him why his heart was having so much trouble, he replied “bases on balls you son of a bitch, bases on balls”.

Best Transaction: traded IF Bill Sweeney to the Chicago Cubs for 2B Johnny Evers (1914). Seven years after Sweeney was traded by the Cubs to Boston because he was blocked by Johnny Evers, the Cubs reaquired Sweeney for Evers. The transaction was highly controversial; Evers was the player-manager of the Cubs by this point and had a public falling out with Cubs owner Charles W. Murphy, who claimed that Evers voluntarily stepped down from being the manager thus allowing him to be traded, a claim Evers strenuously denied. National League owners sided with Evers, and he was allowed to secure a bonus to going to a team that had an established manager. Evers would serve as team captain for the 1914 squad, and the notoriously high-strung veteran infielder was apparently just what the young Braves needed. Evers and Stallings combined to push the team hard down the stretch, making a tremendous 61-16 second half run to win the National League and stun the heavily favored Connie Mack-lead Philadelphia A’s in a four-game sweep in the World Series. The 32-year-old Evers would hit .279/.390/.338 and win the NL MVP award before hitting .438/.500/.438 in the World Series.

George W. Grant, 1921-1922

Grant made his fortune building motion picture theaters in New York and Europe, and purchased the team in 1919. Grant was good friends with New York Giants owner Charles Stoneman and manager John McGraw, and the clubs made so many trades during Grant’s ownership of the Braves that ended up favorably for New York that fans grumbled that the team had turned into a farm

team of the Giants. After Stallings resigned, Grant took a more active role in the front office, but he ended up selling the club after a horrendous 53-100 1922 season.

Best Transaction: traded SS Rabbit Maranville to the Pittsburgh Pirates for OF Billy Southworth, IF Walter Barbare, OF Fred Nicholson, and $15,000 (1921). Maranville was one of the Braves most popular players, but Pittsburgh was desperate for solid defensive play at shortstop, where a ragged cast of characters had filled in since Honus Wagner has retired after the 1917 season. Southworth would end up having one of the most productive three-year runs in Braves history, hitting .315/.371/.448 with 40 stolen bases before getting shipped off to the New York Giants along with top pitcher Joe Oeschger for a package that included player-manager Dave Bancroft and prospect Casey Stengel. Barbare and Nicholson were solid role players.

Southworth would return to the club in 1946 to manage the team for four seasons, including an NL title in 1948.

Christy Mathewson, 1923

Christy Mathewson was a member of the initial baseball Hall-of-Fame class, a legend of the sport who popularized the “fadeaway” pitch (now recognized as the screwball). Mathewson compiled a 635-551 record in 17 seasons with the New York Giants before enlisting in the Army during World War I. During a chemical weapons exercise, Mathewson was accidentally exposed and suffered from tuberculosis that ended his baseball career. With George W. Grant looking to sell the Braves, Giants manager John McGraw introduced Grant to Mathewson and Giants legal representative Emil Fuchs. Mathewson and Fuchs formed a partnership and bought the Braves from Grant, with the idea that Mathewson would be the public face of the group and run the team. After only one season however, it became clear that Mathewson’s health issues would prevent him from continuing the work. While retaining his ownership stake, Mathewson withdrew from the team, and died from tuberculosis in 1925 at the age of 45.

Best Transaction: signed 1B Stuffy McInnis to a one-year, $15,000 contract (1923). McInnis was part of the legendary Philadelphia A’s teams of the early century, and later helped the Boston Red Sox win a World Series in 1918. On the short list of greatest defensive first basemen in major league history, the 32-year-old McInnis maintained a high-average, singles-hitting approach even with the Babe Ruth-lead assault on the game’s offensive records. On a struggling club like the Braves, McInnis’s poise and veteran leadership provided stability, and he hit .315/.343/.392 for the Braves in 1923, earning himself a second $15,000 contract in 1924.

Emil Fuchs, 1924-1935

Despite being a New York lawyer, Judge Fuchs was a die-hard baseball fan who by all accounts was in love with the Boston Braves. He worked hard at selling the team and the game to fans who had largely become enamored by the better and better-run Boston Red Sox. Despite the club reportedly bleeding money, Fuchs would try to capture the headlines with attention-getting trades and signings, like acquiring Rogers Hornsby in 1928. Unfortunately despite Hornsby putting up one of the most impressive offensive seasons in Braves franchise history, the team went 50-103 and Fuchs was forced to sell Hornsby to the Cubs in order to pay down debts. In 1929, Fuchs managed the team himself, mostly as a way to save an expense.

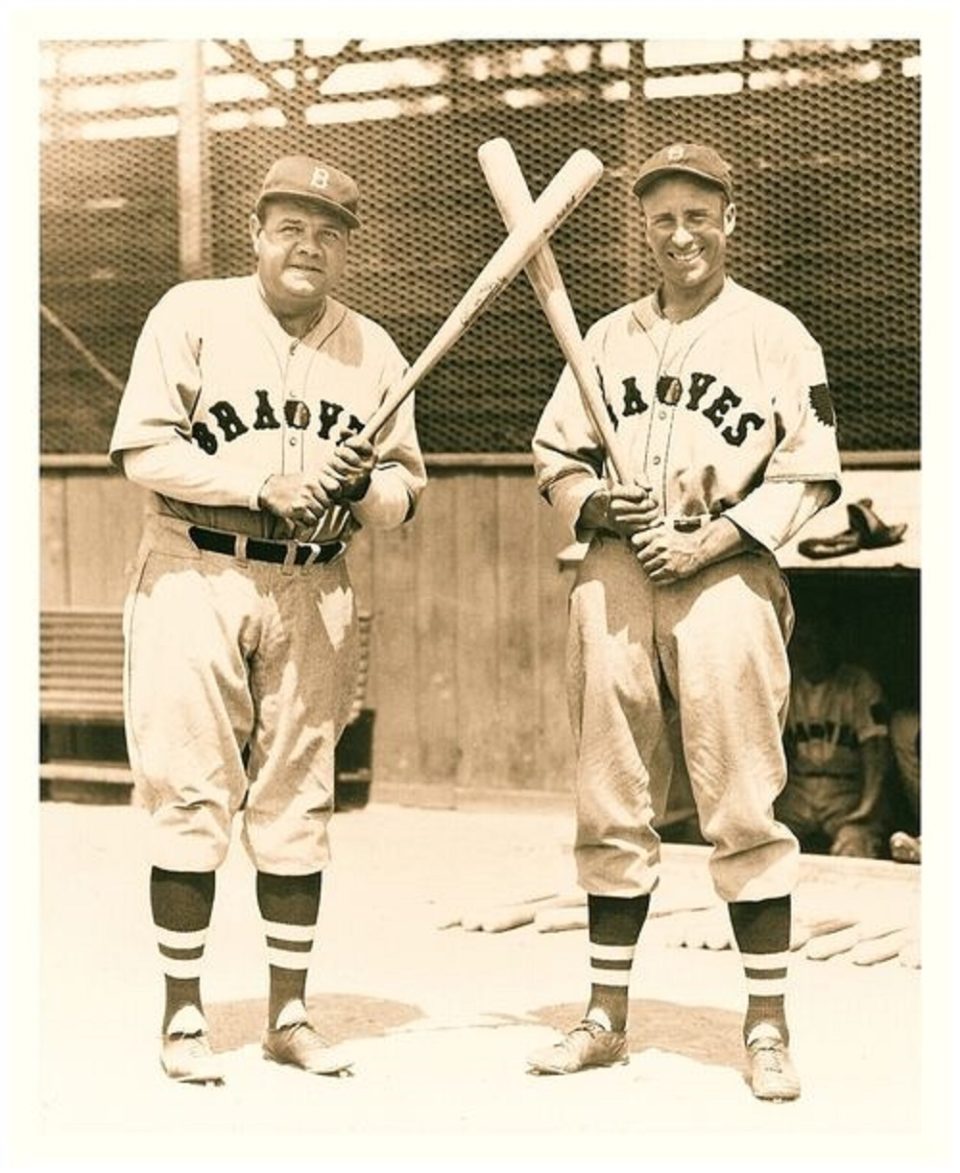

Fuchs would famously try again to capture fans with a flashy signing, persuading the 40-year-old Babe Ruth to return to Boston with a handshake agreement that Ruth would eventually take over as manager. But Ruth’s legs were gone and he only played in 28 games before abruptly announcing his retirement after falling out with Fuchs. As for Fuchs, the Ruth gambit was his last attempt to stay ahead of his creditors, and the National League was forced to step in and take receivership of the franchise after a dismal 38-115 season.

Best Transaction: Traded RHP Art Delaney, OF George Harper and cash to the Los Angeles Angels (PCL) for OF Wally Berger (1929). Berger is on the short list of greatest Boston Braves, and this trade paid near immediate dividends. Berger set the National League home run record by a rookie in 1930 with 38, a mark that stood until Cody Bellinger of the Dodgers broke it in 2017. A four-time All-Star, Berger also lead the NL in homers and RBI in 1935 and is still in the top 10 among all Braves in fWAR. Hand and shoulder injuries would take their toll by 1937 however and would ultimately cut short his career, but for seven seasons Berger was worth the price of a ticket to see the Depression-era Braves.

Bob Quinn, 1936-1945

When a scheme to bring dog racing to Braves Field failed to win the approval of Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis, Judge Fuchs ran out of ways to maintain hold of the club. He was forced to turn over control to minority owner Charles F. Adams, though Adams’s connection to organized gambling made Landis uneasy. He arranged to have the respected Bob Quinn, a long-time baseball innovator who helped build the Boston Red Sox, return to Boston to become president, part-owner, and general manager of the Braves. Quinn is credited with the concepts of farm systems and teams employing professional scouts. The Braves — or the Bees, as Quinn changed the name of the club to for four years — didn’t respond on the field however as the team was still operating on a tight budget. That said, Quinn’s son John Quinn was following his father’s blueprint as the farm director, and this period saw the Braves begin to bring in young talent that would catapult them back to respectability.

Best Transaction: signed LHP Warren Spahn as an amateur free agent (1940). One of those professional scouts that Quinn hired back in his Red Sox days, Billy Meyers, decided to jump ship and work for the crosstown Bees. He was one of the few scouts who liked a skinny Buffalo-area lefty named Warren Spahn. Today, Spahn is on the short-list for greatest left-handed pitchers in baseball history, After three years in the minors and then three years in the military (where his heroism made him the most decorated baseball player of the war, earning him a Bronze Star, Purple Heart, Presidential citation, and a battlefield promotion from sergeant to second lieutenant), Spahn established himself in the majors in his age 25 season and would go on to win 356 games for the Braves, which remains the franchise record.

John Quinn, 1946-1958

The Braves were sold in 1945, this time to a group headed by Boston construction mogul Lou Perini. Perini was able to inject some much needed capital into baseball operations. Rather than pushing out the Quinns and their invaluable baseball experience, both father and son stayed with the organization, but switching roles; son John would become the team’s first modern general manager, and Bob would become the farm director until he was ready to retire a few years later. The alignment of Perini and the Quinns would help bring the Braves its most sustained run of success since the turn of the century, including a NL pennants in 1948 and 1958 and a World Series championship in 1957. Unfortunately the city of Boston wouldn’t see that championship, as consistent attendance troubles would finally chase the club to Milwaukee in 1953.

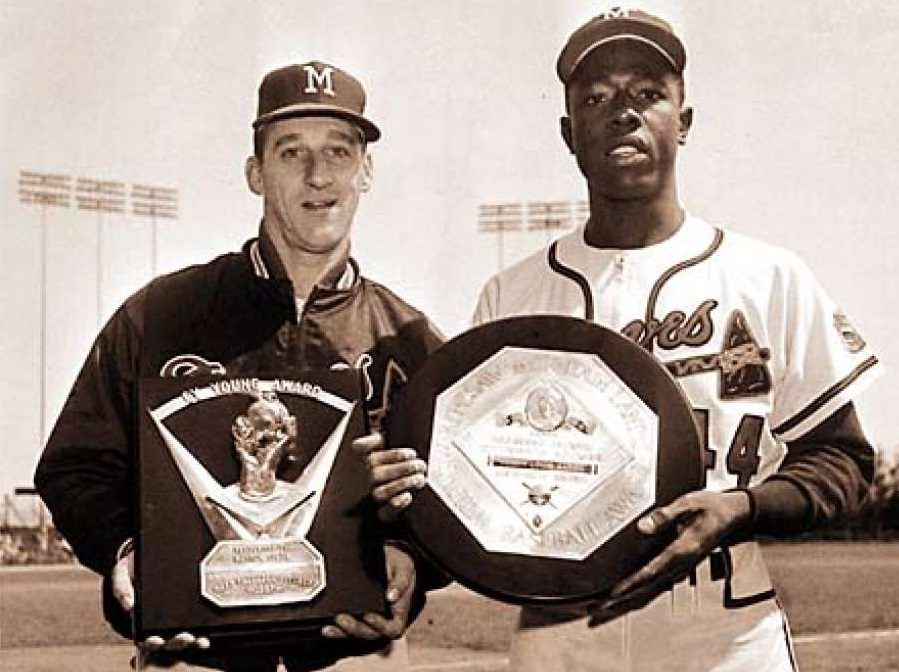

Best Transaction: signed OF Henry Aaron as an amateur free agent (1952). The greatest player in franchise history would join the organization under Quinn, who was among the first general managers to aggressively scout, sign, and develop black ballplayers after the league’s color barrier was finally broken. Quinn signed outfielder Sam Jethroe in 1950 as the fifth black ballplayer in the majors and the first professional black athlete of any sport to play for a Boston-area team. Under the Quinns, the Braves farm system would become the envy of baseball; in addition to Aaron, the system would turn out Hall-of-Famer Eddie Mathews, All-Star catcher Del Crandall, and most of the core of the championship seasons.

John McHale, 1959-1966

The 1958 NL championship team would be the last hurrah for both the Braves for several decades and for baseball in Milwaukee for even longer. Seeking new challenges, or perhaps foreseeing a decline in a talented but aging roster, John Quinn left the Braves to take over what would be a successful rebuild of the Philadelphia Phillies. Quinn recruited Tigers GM John McHale to replace him. Only 35 when he took over the Braves, McHale watched the Braves finish in 2nd place in 1959 and ’60, then slip into the second division. Trades of established players for young players didn’t bring in enough talent and the farm system dried up. By 1962, attendance in Milwaukee slipped to under 1 million a year and would stay under that mark until owner William Bartholomay. who had purchased the Braves from Lou Perini in 1962, moved the franchise once again, this time to Atlanta.

Best Transaction: selected 2B Felix Millan from the Kansas City Athletics in the first-year player draft (1964). Most of McHale’s early tenure was spent selling off pieces of the late 50’s championships squads to acquire younger talent to match with the still-potent Hank Aaron, efforts that went largely unrewarded. As the team was preparing the move to Atlanta, McHale used the little-regarded first-year player draft to acquire Félix Millan, a Puerto Rican second baseman who had just completed his first minor league season in the A’s farm system. The first-year player draft was a mechanism owners used to try to prevent teams from paying high bonuses for amateur talent. Players who had been in affiliated ball for one season were eligible to be drafted, with the team losing the player being compensated $25,000 by the drafting team, unless the player was protected on the major league roster. The idea was that teams wouldn’t play large bonuses to amateur players if they knew there was a possibility of losing those players for a fixed price.

It didn’t really work as designed, and in 1965 MLB initiated the Rule 4 amateur draft, essentially the same draft used as the primary method to acquire North American talent today.

Millan would reach the majors in the inaugural season in Atlanta and be a mainstay for seven seasons, hitting .281/.319/.349 with 56 stolen bases, winning two Gold Gloves, and making 3 All-Star teams before being traded to the Mets in an ill-advised transaction in 1972.

Leave a Reply