See also: Index of Best Braves by Uniform Number

The day I become content is the day I cease to be anything more than a man who hit home runs.

– Henry Aaron

It probably goes without saying to anyone reading this website that Henry “Hank” Aaron was the greatest player every to don a Braves uniform of any number. And we’ll get to the numbers and the accomplishments in just a few paragraphs.

But first a few words about Henry Aaron, the man. The words “hero”, “legend”, and “iconic” get thrown around a lot these days, many times for people that are not any of those. To me, what made Aaron all of those things wasn’t just his on-field accomplishments, his work as one of the first African-Americans in a leadership role in a major league front office, or even his status as a civil rights leader. What Aaron did was give everyone — especially white Americans like myself — an honest and unflinching look at what unfiltered racism can do to someone.

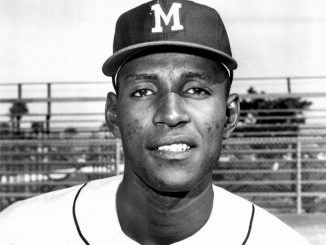

Aaron was no stranger to racism, having grown up in the Jim Crow South. When Aaron was sent by the Braves to the class-A Jacksonville Tars farm team in 1953, he and teammates Horace Garner and Felix Mantilla broke the color barrier for the South Atlantic League which had first started in 1904. On the field, Aaron was a star — he lead the league in batting, runs, and RBI — but off the field he could not dine out with teammates or share road accommodations. Aaron and almost all of the black ballplayers looking to break into the majors then followed the path blazed by Jackie Robinson in the Dodgers system: don’t respond to taunts, stay away from controversy, turn the other cheek.

Aaron would break camp with the Milwaukee Braves the following season after a spot opened up when starting left fielder Bobby Thomson broke his ankle sliding into second base in an exhibition game. Aaron made his major league debut on April 13, 1954, playing left and going 0-for-5 against Joe Nuxhall of the Reds. He would finish the season with 13 home runs and a .280/.322/.447 battling line — the last time he would slug under .500 in the next twenty seasons — and finished fourth in Rookie of the Year voting.

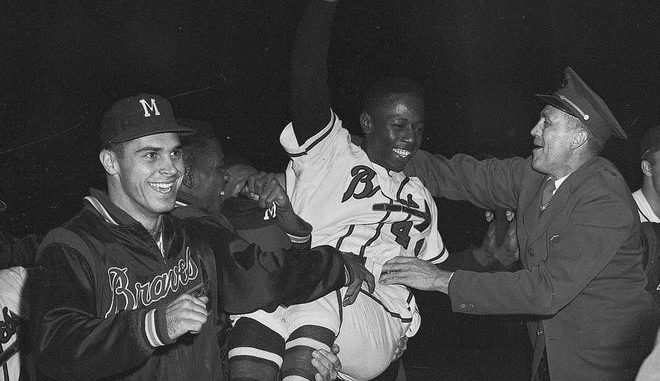

In his sophomore season he hit .314/.366/.540 and earned the first of his 21 consecutive All-Star appearances. In his third year, his first wearing #44 after wearing #5 his first two seasons, he won the NL batting title, and in his fourth he won is first and only MVP title after leading baseball in HR (44) and RBI (132) and hitting .322 to flirt with the Triple Crown, and then went on to hit arguably the biggest home run in Braves history: a two-run walk-off shot against St. Louis to clinch the NL pennant for Milwaukee. The Braves would go on to face and defeat the New York Yankees in the World Series. Aaron went 11-for-28 with 3 home runs and 7 RBI in the 7-game series.

The previous paragraph would be impressive highlights for someone over the course of their whole career. For Aaron, it was just the start. He would pile more 645 home runs, 1898 RBI, three Gold Gloves, another batting title, four RBI crowns, and two more playoff appearances onto the rest of his career.

Aaron was essentially already a Hall-of-Famer when the Braves moved from Milwaukee to Atlanta before the 1966 season. Two years later he would break 500 home runs in his career, the first by a Brave; two years after that he would become the first Brave to reach 3000 hits.

Aaron was initially concerned about the team’s move to the Deep South. He told the Washington Post, “I have lived in the South, and I don’t want to live there again. We can go anywhere in Milwaukee. I don’t know what would happen in Atlanta”. Aaron was encouraged by other prominent black sports figures of the time, like Jim Brown of the NFL and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar of the NBA who were also outspoken in the civil rights arena. They and other civil right leaders understood what the powerful statement of having the biggest star on the first major league professional team in the Deep South being a black man would make. So Aaron made the move with the Braves and kept his incredible career alive. And for the most part, the city embraced their new star and Aaron came to love the city back.

Passing Ruth

In Atlanta, Aaron had almost had a second Hall-of-Fame career. While the Braves would never come back to their 1957-58 Milwaukee heights during Aaron’s tenure with Atlanta, they would play in the very first NCLS in 1969, losing to the “Miracle Mets” in 3 games despite Aaron going 5-for-14 with 3 home runs. As the 1972 season started (belated thanks to a player strike), Aaron was approaching Willie Mays‘ National League home run record; Mays was still active in ’72 but winding down his own incredible career with the New York Mets. Aaron was still playing at a high level, and it seemed to catch much of baseball by surprise that Aaron was close to the rarified air of the top of the all-time home run records, likely due to having a strong but steady career in two smaller-market cities in Milwaukee and Atlanta rather than the more media-heavy New York and San Francisco for Mays.

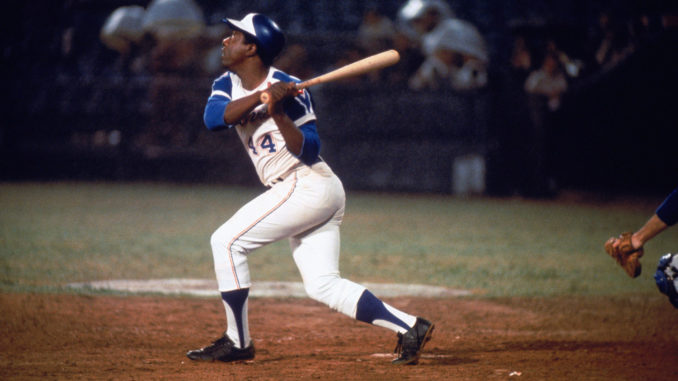

Aaron surpassed Mays in home runs in 1972. He also passed Stan Musial‘s then major-league record of 6134 total bases; he would end his career with 6856 total bases, still the major league record, one that Aaron would say was his favorite statistical accomplishment.

Aaron was only two home runs short of Babe Ruth‘s all-time home run record as the ’72 season came to a close. Aaron, who had lived with the reality of American racism his whole life, would experience a pressure cooker of hatred beyond anything he had experienced before. Aaron received hundreds of death threats, both for him and threatening retaliation against his family if he surpassed Ruth. He had to hire a bodyguard and send his kids to private school that afforded more security. His college-age daughter received hate mail and was advised not to leave the school grounds. When spring training rolled around, Aaron stayed at a separate, secret hotel from the rest of the team, and slipped out the back door of stadiums after games.

“I could see when he got a bad letter,’’ teammate Dusty Baker recalled. “He’d drop it and go into the trainer’s room. One said, ‘Get out of here [slur].’ Another one saying somebody in a red jacket’s going to shoot him. Me and [teammate] Ralph Garr were like, ‘We’ll be with you.’ We were looking up in the stands, more scared that something would happen than Hank was. Hank just went ahead with his life.’’

Aaron later revealed that he received more than 900,000 letters in total — many in support of him, but many vicious and brutally racist.

Inevitably Aaron did pass Ruth on April 8, 1974, the Braves home opener. The relief was palpable.

What a marvelous moment for baseball; what a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia; what a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol. And it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron.

And for the first time in a long time, that poker face of Aaron shows the tremendous strain and relief of what it must have been like to live with for the past several months.

– Vin Scully, Dodgers television call

Aaron would hit 41 more home runs before calling it a career, a home run record that would stand for forty years until Barry Bonds hit his 756th career home run in 2007. After spending his final two seasons with the Milwaukee Brewers, where he would set a new major league career RBI record which he still owns, Aaron would return to the Braves to work in the front office in 1976.

In 1982, Aaron was named a Braves vice-president and Director of Player Development, becoming one of the first African-Americans to hold a high-level front office position for a major league club. Aaron would continue to stay busy, working in executive positions for the Braves, Turner Broadcasting, and the commissioner’s office – often simultaneously – while also launching a successful automobile dealership franchise.

I Had A Hammer

In 1990, Aaron had published his autobiography I Had a Hammer. An unflinching look at not just his legendary baseball career, the book is a testimonial of what it was to grow up in the Jim Crow South, and the senseless obstacles a talented black man had to overcome just to play baseball in America. His unsentimental recount of the Ruth chase alone makes it one of the best and most powerful autobiographies of both a baseball player and a civil rights icon.

Honorable Mention

Only two other Braves have worn #44, veteran reliever Bob Chipman in parts of 1951 and journeyman infielder Buzz Clarkson in 1952. Neither of these gentlemen had a particularly distinguished career with the Braves, but they kept the number warm for the Hammer.

Who Is the Best Ever To Wear #44?

Aaron isn’t the only baseball great to wear #44. Hall-of-Famers Reggie Jackson and Willie McCovey wore the number as well, as did some fine pitchers like David Cone, Roy Oswalt, and Jake Peavy.

But it’s Aaron, and it always will be. Just to wrap this up here’s what the back of his baseball card would contain.

- 755 home runs (2nd all-time, 1st all-time for the Braves)

- 2174 runs scored (tied w/Ruth for 4th all-time, 1st all-time for Braves)

- 2297 runs batted in (1st all-time)

- 240 stolen bases (6th all-time for Braves)

- 1267 walks (27th all-time, 3rd for Braves)

- .293 batting average (13th all-time for Braves)

- .378 on-base average (7th all-time for Braves)

- .567 slugging percentage (24th all-time, 1st all-time for Braves)

- 1 MVP (1957), 13 top-10 MVP finishes

- 3 Gold Gloves

- 19 All-Star Games (all consecutive)

- .357/.405/.710 post-season batting line

Leave a Reply