When my brother Andy Harris asked me if I’d like to contribute to the Best Brave By Uniform Number series, I agreed thinking I’d do a “Let’s Remember Some Guys” piece on one of the semi-obscure-to-normie bullpen arms from the 90’s I grew up on. I saw #43 was available, and bingo. Mark Wohlers, quintessential 90’s Braves bullpen guy! I checked what other players had worn #43 for the Braves, and the list is quite expansive – Julio Teheren, but only in his first call-up. Terry Mulholland. Luis Avilan. Scott Proctor. Odalis Perez. Kyle Farnsworth. Tim Spooneybarger. Micah Bowie. Cito Gaston. Bob Walk. Rico Carty.

Oh, wait, Rico Carty. Before my time, but he was supposed to be semi-legendary. Not being quite the big baseball nerdwad on the level of my brother (I picked #43 because I’m a big NASCAR nerdwad), I took a look into Mr. Carty’s life and career, and madre de dios!

Rico “Beeg Boy” Carty was the first MLB superstar from San Pedro de Macorís, Dominican Republic. This city evolved into a baseball powerhouse thanks to the construction of numerous postwar American-owned sugar mills, each with its own baseball diamond for American managers and their families, with an influx of Dominican and non-Dominican Caribbean immigrants looking for work. This turned San Pedro de Macoris into the place that has produced more major league talent than anywhere else on Earth. This one town produced 37 major league ballplayers from 1938 to 2001.

Carty was a major leaguer for the Braves from 1963-1972, moving with the franchise from Milwaukee to Atlanta during that span. He slashed .317/.388/.496 for the Braves in 3098 PAs, most but not all of it while wearing #43 – he got his 1963 big league cup ‘o coffee as #77, and then switched to #25 in 1969. That’s major production, and garnered some MVP votes in 1969 and 1970. In 1970 he had his best season in the big leagues – he won the NL batting title, hitting .366 in 560 PAs, adding 25 homers for an OPS of 1.037. It was a monster of a season that included a 31-game hitting streak, a Braves record that would stand until it was predictably shattered by the unstoppable legend Dan Uggla in 2011. He was also the first ever player to be voted into the All-Star game as a write-in that year, beating out Pete Rose to start in the NL outfield next to Hank Aaron and Willy Mays.

Carty ended up amassing career numbers worthy of high esteem as a pure hitter, hitting a lifetime .299/.369/.464 in the big leagues. That said, Rico Carty managed to pick up a few labels in his career that no doubt played a role in limiting his overall production – “injury-prone”, “defensively-challenged”, and “temperamental”. Let’s look at those labels, and provide some context.

Injury-Prone. Carty missed all of the 1968 and 1971 seasons due to illness or injury and had chronic back, knee, and elbow issues that kept him out of the lineup frequently, and far more than his fair share of freak incidents.

The reasons he missed multiple full seasons were a mild case of tuberculosis in ‘68 and a knee injury due to an outfield collision with Matty Alou in winter ball described by a team doctor as “as bad a knee injury as an athlete can have.” He had complications with blood clotting while recovering from it. The fact that he played again after either issue, and at a high to above-average level, is a testament to his toughness. Physical issues also had an adverse effect on his defense. It wasn’t until he was already in the majors before a doctor discovered his right leg was shorter than his left, leading to all kinds of subconscious physical compensations that left him open to back problems. Those got better once he started wearing corrective shoes. Developmental damage was already done though, and a once-promising catching prospect got shuffled around the diamond to positions he wasn’t as comfortable with (or, to be fair, interested in).

Defensively-Challenged. Originally a catcher, he was tried at first base, third base, and the outfield to try and limit his defensive exposure. He ended up primarily as a left fielder in order to minimize the damage he could do to his own team with a glove in his hand. He still managed to post an impressively terrible .975 fielding percentage as an outfielder during his Braves career. One writer described his defense as “amusing at best.” The DH was introduced during his career, and he was seen as the poster-boy for the position, and was traded to the AL in hopes that he would take advantage of it (he didn’t want to).

Temperamental. Carty punched fans and umpires, fought cops, nearly crashed the team plane fighting with Hank Aaron, feuded with Eddie Matthews, and threw Frank Robinson under the bus as a bad manager at an event held in Robinson’s honor.

That said, Carty was neither a selfish nor entitled personality seeking to elevate himself at the expense of his team. Most teammates loved him (despite the previously mentioned altercation with Aaron, the two were very supportive of each other through their lives), and he was one of the first fan-favorites for the new-to-MLB Atlanta Braves when the team moved in 1966. He absolutely did not put up with disrespect however, and would stand up to it with no regard as to whom it came from, and much of that disrespect came in the form of racism. Fans, cops, umpires, and teammates who presented racism to him had it confronted right then and there. The same went for any other kind of dispute, Carty did not mess around with anyone. He was almost always in the right in all of these disputes. For example, two racist off-duty Atlanta officers started a fight with Carty and his younger brother. Carty got blackjacked in the face and suffered serious injury to his eyes. Carty and his brother were arrested, the off-duty officers were not. Thanks to Carty’s fame, the issue wasn’t swept under the rug, and the blatant brutality and misconduct by the two assailants and the arresting officer who let the other two walk led to all three cops being suspended and a public apology issued to Carty by then-Atlanta mayor Sam Massell.

Carty returned to the Dominican Republic after his playing days, and has a foundation devoted to charitable and humanitarian support that he continues to be involved in. He was the first breakout star in MLB from the Dominican Republic and is regarded as a hero in the community. #43 Rico Carty is one of the most outstanding and authentic human beings to ever walk the planet.

For more on the amazing career of Rico Carty, check out the SABR piece by Wynn Montgomery, this 2018 interview with Armando Soldevia, for La Vida Baseball, and this fantastic interview on the Behind the Braves podcast.

Honorable Mention:

- A strong honorable mention goes to current Braves manager Brian Snitker, who is currently #43 for the Braves. An argument can be made that Snitker’s contributions while wearing that number outrank Carty’s 1963-1968 seasons with the Braves, but I’m not going to make that at this time. After a 39-year career in the Braves minor leagues as a player, coach, and manager, Snitker was tapped to take over the big league club midway through the 2016 season. Sniker now has a 441-390 win-loss record in the majors, guiding the Braves to four consecutive NL East pennants, two NLCS appearances, and a World Series win in 2021.

- In the first iteration of this series, Brent Blackwell tabbed 1995 World Series-clinching closer Mark Wohlers as the greatest Brave to wear #43, with Carty taking #77, the number he wore only for his rookie season in 1963. That was a way to honor both Carty and Wohlers since at the time there was no other player in Braves history to wear #77 in the big leagues. Since then however Luke Jackson has done a more-than-credible job with #77, so it seemed to make sense to put Carty with the number he was most associated with during his Braves career. You can read Brent’s original Best Braves To Wear #43 post on Mark Wohlers here.

- Before Carty, platoon outfielder Wes Covington was a key part of Milwaukee’s back-to-back World Series appearances in 1957-58, hitting .305/.358/.577 with 45 HR and 139 RBI over those two seasons. Covington played 6 of his 11 major league seasons with the Braves, hitting .284/.336/.473 with 65 homers total as a left-handed platoon player and pinch-hitter.

Who Is the Best Ever To Wear #43?

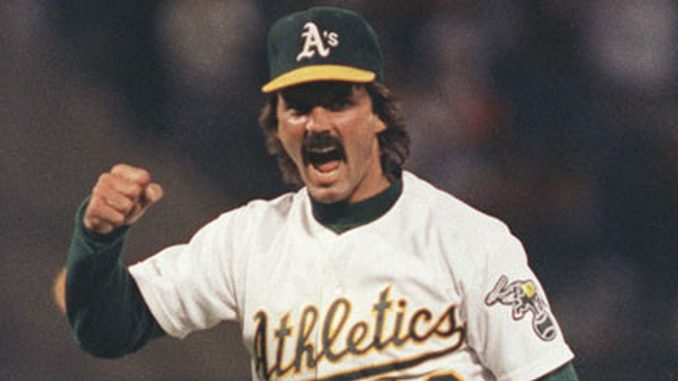

Other than his first three seasons, Hall of Fame reliever Dennis Eckersley wore #43 for the remainder of his 24-year career. Eckersley is one of 3 players to earn both the Cy Young Award and the MVP as a relief pitcher, taking the honors with a 1992 season that saw him convert 51 of 54 save opportunities while finishing 65 games with a 1.91 ERA. Of the 13 major league pitchers that have amassed 350 or more career saves, Eckersley blows the others away in career innings pitched — 3285.2 — thanks to serving as a starting pitcher for the first half of his career.

Leave a Reply